My Opinion: Orthodox Jewish community in Brooklyn, NY is plagued with mental health and drug addiction problems due to the social isolation, oppression, and indoctrination. Orthodox Judaism as the creation of Abwehr; Orthodox Jews and money laundering for the New Abwehr and Russian mob: "Orthodox Judaism" as a sect was created by the German Military Intelligence for the money laundering and espionage purposes after WW1 ...

-Orthodox Jewish community in Brooklyn, NY is plagued with mental health and drug addiction problems due to the social isolation, oppression, and indoctrination - Google Search https://t.co/1Ste2oMZf0 pic.twitter.com/v5RTpq1QqE

— Michael Novakhov (@mikenov) July 27, 2023

-Orthodox Jews and money laundering for the New Abwehr and Russian mob - TOC - Google Search https://t.co/taqBl25FRm pic.twitter.com/gaHXldpWFk

— Michael Novakhov (@mikenov) July 27, 2023

7.27.23 - Orthodox Judaism as the creation of Abwehr

- Orthodox Judaism as the creation of Abwehr - Google Search

- orthodox judaism - Google Search

- orthodox judaism - Google Search

- Modern Orthodox Judaism: A Documentary History on JSTOR

- Rescued from the Reich: How One of Hitler’s Soldiers Saved the Lubavitcher Rebbe on JSTOR

- Abwehr and Orthodox Judaism - Google Search

- Orthodox Judaism - Wikipedia

- Orthodox Jews and money laindering for the New Abwehr and Russian mob - TOC - Google Search

- Orthodox Jews and money laundering for the New Abwehr and Russian mob - TOC - Google Search

- "Orthodox Judaism" as a sect was created by the German Military Intelligence for the money laundering and espionage purposes after WW1 - Google Search

- "Orthodox Judaism" as a sect was created by the German Military Intelligence for the money laundering and espionage purposes after WW1 - Google Search

- Orthodox Jewish community in Brooklyn, NY is plagued with mental health and drug addiction problems due to the social isolation, oppression, and indoctrination - Google Search

- Orthodox Jewish community in Brooklyn, NY is plagued with mental health and drug addiction problems - Google Search

- Orthodox Jewish community in Brooklyn, NY is plagued with mental health and drug addiction problems - Google Search

- Michael Novakhov on Twitter: "Orthodox Jewish community in Brooklyn, NY is plagued with mental health and drug addiction problems - Google Search https://t.co/viP0M1i1CN https://t.co/IaiLvpvmqs" / Twitter

- Michael Novakhov on Twitter: "Orthodox Jewish community in Brooklyn, NY is plagued with mental health and drug addiction problems due to the social isolation, oppression, and indoctrination - Google Search https://t.co/1Ste2oMZf0 https://t.co/v5RTpq1QqE" / Twitter

- Michael Novakhov on Twitter: ""Orthodox Judaism" as a sect was created by the German Military Intelligence for the money laundering and espionage purposes after WW1 - Google Search https://t.co/VrsuRKcJuk https://t.co/EwL48aocQO" / Twitter

- Michael Novakhov on Twitter: ""Orthodox Judaism" as a sect was created by the German Military Intelligence for the money laundering and espionage purposes after WW1 - Google Search https://t.co/2h5oVPu4QA https://t.co/JnvaOXgCMJ" / Twitter

- Michael Novakhov on Twitter: "Orthodox Jews and money laundering for the New Abwehr and Russian mob - TOC - Google Search https://t.co/taqBl25FRm https://t.co/gaHXldpWFk" / Twitter

- Michael Novakhov on Twitter: "Abwehr and Orthodox Judaism - Google Search https://t.co/7ZHIrLhOhM https://t.co/xcSs0GpZUs" / Twitter

- Michael Novakhov on Twitter: "Orthodox Judaism and the Politics of Religion https://t.co/FqEXNA9CXK https://t.co/bOzP7M93aV" / Twitter

- Michael Novakhov on Twitter: "Rescued from the Reich: How One of Hitler’s Soldiers Saved the Lubavitcher Rebbe on JSTOR https://t.co/SPFQSntGU1 https://t.co/NUNKKPvf6Q" / Twitter

- Michael Novakhov on Twitter: "Modern Orthodox Judaism: A Documentary History on JSTOR https://t.co/93eR8iznfJ https://t.co/vOjBMss1ND" / Twitter

- Michael Novakhov on Twitter: "orthodox judaism - Google Search https://t.co/k2xFuju9Lf https://t.co/pcmTbk1cu0" / Twitter

- Michael Novakhov on Twitter: "orthodox judaism - Google Search https://t.co/k2xFuju9Lf" / Twitter

- Michael Novakhov on Twitter: "orthodox judaism - Google Search https://t.co/9skuHk5VDg https://t.co/Y6C0SaOcYT" / Twitter

- Money Laundering Keeps ultra-Orthodox Families Afloat - Business - Haaretz.com

- A Portrait of American Orthodox Jews | Pew Research Center

- orthodox judaism - Google Search

- Orthodox Judaism and the Politics of Religion

- Orthodox Judaism as the creation of Abwehr - Google Search

Psychoanalysis of intelligence operations and psychohistory of abwehr - 5.2.23

During World War II, Jews were overrepresented in combat units in Allied armies and in resistance forces operating all over Europe. Many Jews carried rifles, parachuted behind enemy lines, flew fighter and bomber aircraft, and did a host of other jobs that helped the war effort. But a few managed to make an impact in a much bigger way. This is the story of one such Jew from Italy, who fought the Nazis without ever firing a shot. His name was Renato Levi and he changed the face of the war in the Middle East.

After the war Levi’s story was classified, his files locked away and his accomplishments forgotten. When Levi died in 1954 his story almost died with him. Only recently have historians been uncovering more information about the Jew who fooled the Germans and changed the course of the war.

Levi was recruited as a spy by the Germans in his native Genoa in 1939. After being approached by the Germans he went to the British Consulate and offered to secretly work as a double agent. The British instructed Levi to allow himself to be recruited by the Germans while maintaining contact with them. He followed their orders and the Germans sent him to Paris, where the British connected him with the French secret service, the Deuxieme Bureau. There he was shared by both countries while pretending to spy for Germany. But the German victory over France was so swift that the Germans had no need for a spy in Paris, so he was soon recalled to Genoa and given a new mission.

He was instructed to head to Cairo to be their spy at the center of the British war effort in the Middle East. Levi traveled to Egypt via neutral Turkey, where he reestablished contact with British intelligence. They spirited him to Palestine to debrief him with the aim of making sure that he was still working for the Allied cause. The declassified intelligence report of that debrief lays bare Levi’s motivation:

His motives for working for us are difficult to fathom. He is, of course, a Jew and says he wants to do something to help the Allied cause because it is fighting on behalf of the Jews. In addition, he obviously has considerable love of adventure, and enjoys the work for its own sake. He is very fond of women, and the work gives him ample opportunities of travel, and of handling large sums of money, which he would not otherwise get. He showed no particular dislike of the Germans or the Italians; in fact he often described the good times the Germans had given him.

After being cleared by the intelligence services, Levi was sent on to Cairo and handed to a shadowy intelligence unit named A Force. This was the British intelligence team in charge of disinformation in the Middle East. With the German army bearing down on Cairo, A Force needed to bring Levi, their new double agent, into play. But they faced a dilemma; Levi had been told by the Germans that a wireless radio set would be sent to him once he was in Cairo and he was to use it to transmit information to them. No wireless set ever materialized. Without a way to contact the Nazis to pass them disinformation, A Force commander Dudley Clarke decided to send Levi back into the arms of the enemy.

This was no small task, and it involved Levi agreeing to travel back to Italy via neutral Turkey and then crossing into the Third Reich, while the Holocaust was taking place, to walk into the arms of German intelligence and lie to their faces. The only thing A Force could offer him to help in this endeavor was a cover story. He was to tell them that he had successfully made it to Cairo and bought a wireless transmitter from an Italian hiding in Egypt, an Axis sympathizer called Paul Nicossof, who could send wireless transmissions in Morse code. A Force needed Levi to give German intelligence the correct frequencies and make sure the Germans intercepted “Nicossof’s” transmissions. Of course in reality there was no Nicossof, just an A Force wireless expert transmitting false information. Levi had been instructed by A Force to tell German Intelligence to intercept transmissions from Nicossof twice a week starting on Monday the 25th of May.

The cover worked. The Germans not only intercepted the messages, but they also reacted to them in precisely the way the British needed. The first big success was convincing the Germans not to trust their other intelligence sources regarding an upcoming British offensive. As a result, Operation Crusader caught Rommel by surprise when it was launched on Nov. 18, 1941. Commonwealth forces pushed the Axis army back across the desert into Libya, leading to the liberation of the port of Tobruk.

A year later, the British managed to fool the Axis again in preparation for the El Alamein offensive. In October 1942, A Force transmitted to German intelligence that the British build-up of forces was to be used to invade the Mediterranean island of Crete rather than launch an offensive in North Africa. Hitler ordered the island reinforced with units that otherwise would have been available to fight at El Alamein 10 days later. Rommel and his Afrika Korps were defeated and pushed back across North Africa, never to return.

The disinformation transmissions to the Germans continued throughout the war covering operations around the Mediterranean theater. But the British never directly heard from Levi, the man responsible for making it all happen, after he left Turkey. The spymasters of A Force only knew that the Germans had started responding to their wireless transmissions, so they assumed that Levi had managed to fool them.

In actuality, being back in Axis territory proved incredibly dangerous for Levi. A former French agent known as “Jean” recognized Levi as having worked for the Deuxieme Bureau and warned the SS that he had been a French agent. This led to some tense conversations between Levi and his German handlers but he managed to convince them that he was still their man.

Then he was arrested by the Italians who accused him of “having cooperated with the British Intelligence Service in Belgrad [sic] (Yugoslavia) and in Cairo.” The Italians interrogated him over a period of several months. Levi’s German intelligence handlers refused to intervene. Despite repeated interrogations, Levi proclaimed his innocence. He was held for months without trial but never confessed to having spied for the British, only for the Germans. He suspected that he had been set up but was never sure.

During his eventual trial, Levi was asked if he was “of Jewish faith” and responded that “he was of Jewish origin but Catholic by religion.” The next day he was sentenced to “five years confinement as a political prisoner for being socially dangerous.” He served most of his sentence in a prison on Tremeti, a small island in the Adriatic. He was eventually moved to a facility on the Italian mainland where he was liberated by the British army in October 1943.

Once liberated, Levi made his way back to A Force who’d had no idea what had happened to him. He explained his arrest, interrogation, and eventual imprisonment. They gave him 1,500 pounds for his efforts and another 2,000 pounds compensation and sent him on his way. Levi died in 1954 in Italy. His story died with him, until researchers discovered his files when they were declassified over 50 years later.

The files revealed how the succession of events in Levi’s life coalesced to make him into a natural spy. He was born in Genoa, Italy, in 1902 to an assimilated Italian Jewish family. His parents moved to India in 1910 where he became a British subject and fluent in English. A few years later Levi was sent to Switzerland to complete his education where he learned to speak German and French like a native. He had a thirst for adventure which led him to try his hand at becoming a businessman in Australia. He joined the Australian Italian chamber of commerce, he even served as a witness in a robbery trial. He ended up going bankrupt and trying to flee the country only to be arrested by Australian police. A judge ordered he be held until he coughed up the cash he owed. These experiences would have served him well later as he was interrogated and cross-examined by the Italian security services.

The word “Jew” catches the eye when reading through the declassified intelligence files. It follows Levi through all the reports on his activities. He was even described as being “of Jewish appearance” by the British intelligence officer who debriefed him. There is no evidence of Levi hiding his Jewish identity from the British, Germans, or Italians nor any evidence of it impacting his ability to carry out espionage, though as we have seen it did come up at the end of his trial.

But why did the Germans recruit a Jewish spy? A historian at the Holocaust Educational Trust Martin Winstone told Tablet that he suspects the reason may have been the involvement of the less ideological Abwehr (German military intelligence). “The Abwehr was not led by ideological Nazis and its head Wilhelm Canaris was involved in many of the military plots against Hitler. This does not necessarily mean that these people were free from antisemitism themselves, but there was perhaps a more pragmatic approach than other organizations such as the Gestapo when it came to intelligence operations.” There are references in the British intelligence reports to the Abwehr and the even less ideological Italians playing a role in handling Levi.

Tablet contacted one of Levi’s surviving relatives, his great-nephew Kee Levi, to find out more about him.

“He was always a bit of a black sheep in the family; he was always going to my grandfather because my grandfather was always bailing him out,” Kee confides. “I’m so glad he survived the war because I think that so many people like him didn’t!” he added. “Immensely brave some of the things he did. Foolhardy, really.”

The story of the bitter rivalry between two Jewish agents in World War II has led one historian to speculate on the many different ways the war could have played itself out

Get email notification for articles from Liza Rozovsky Follow

Aug 6, 2022

Get email notification for articles from Liza Rozovsky Follow

Aug 6, 2022

At the height of World War II, Samson Mikicinski, a Jewish Polish-Russian businessman, rescued top models, society women and female relatives of exiled Polish leaders from occupied Warsaw and smuggled them to Paris. During the same period, Edward Szarkiewicz, a Jew who was born in the Lviv Oblast of Ukraine, converted to Christianity and operated as a British mole working within the Polish security service. The encounter between them is the subject of a recently published book by historian Yaacov Falkov, “Between Hitler and Churchill: Two Jewish Agents and the Effort Made by British Intelligence to Prevent Secret Polish-Nazi Collusion” (Magnes Press; Hebrew).

1University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, Canada

2Jewish Child and Family Service, Winnipeg, MB, Canada

3Department of Psychology, University of Winnipeg, 515 Portage Avenue, Winnipeg, MB, Canada R3B 2E9

Received 2015 May 12; Accepted 2015 Jun 7.

This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Awareness of addictions in the Jewish community is becoming increasingly prevalent, and yet, a gap exists in the literature regarding addictions in this community. Knowledge about the prevalence of addictions within Jewish communities is limited; some believe that Jews cannot be affected by addictions. To address this gap, a pilot study was conducted to gather preliminary evidence relating to addictions and substance use in the Jewish community. Results indicate that a significant portion of the Jewish community knows someone affected by an addiction and that over 20% have a family history of addiction. Future research needs are discussed.

Approximately 11% of the Canadian population struggles with substance use [1]. The prevalence of alcohol and substance use in the Jewish community remains uncertain, possibly due to the existence of some denial of addictive behaviours in this community [2]. Israeli evidence documenting the lifetime prevalence of drug use in Israel is 13% (as cited in [2]). Yet, to date, it appears that a large portion of the North American Jewish community views alcoholism as an illness, has a strong fear of alcoholics, and blames individuals with addictions for their condition [3, 4]. One possible conclusion is that Jewish people believe that members of the Jewish community simply do not become alcoholics, so they are convinced that they are not exposed to people with addictions [5]. Therefore, they lack the ambition to seek education on the topic and become naive to the reality of the prevalence of addictions in the Jewish community [5]. Glass [6] discusses the myth existent across Jewish communities that Jews cannot have addictions. “Over the years, this long legacy of denial among Jews has resulted in unnecessary pain, heartache, and a great deal of alienation from Judaism by those suffering from addiction. It has also served to prevent some suffering Jews from seeking or accepting appropriate help” [6, page 235]. The refusal of Jewish alcoholics is also shown when a large number of Jewish people claim that they do not know any heavy drinkers [3]. These views contribute to an active denial stage in Jewish addicts [5]. The belief that Jews do not become alcoholics results in leaders of the community failing to address the problem and discourages health professionals to conclude the diagnosis of an addiction of a Jewish person [5]. While these views may have changed on a societal level, empirical evidence on this topic remains limited, resulting in outdated reflections of addictions in Jewish populations which may not accurately represent the current reality. For instance, Jewish Alcoholics, Chemically Dependent Persons, and Significant Others, commonly known as JACS, is a self-help program for Jews and loved ones coping with addictive behaviours [6]. JACS groups are located throughout Canada, the United States, Australia, Brazil, and Israel [7] and are indicative of the existence of addictions in Jewish communities internationally.

Jewish individuals are likely to be impacted by addictions, similar to other ethnicities [8]. However, due to the stereotype that Jews cannot have addictions [5, 9], Jews affected by addictions may find themselves with limited supports within their own communities [5]. The purpose of this study is to provide preliminary evidence relating to addictions and substance use in the Jewish community.

A survey was administered to adults receiving services through Jewish Child and Family Service, Winnipeg location. A package was mailed to randomly selected individuals, where they were asked to fill out the questionnaire and mail it back to the Jewish Child and Family Service office. The package mailed to participants included a guide detailing the contents of the package, a consent form, a questionnaire, a feedback form, a Jewish Alcoholics, Chemically Dependent Persons, and Significant Others (JACS, a Jewish 12-step group) bookmark, and a stamped envelope to mail the package back once completed. Participants were contacted two weeks after packages had been sent in order to inform them that they have been randomly selected to participate in the study and to provide an opportunity to ask questions and express concerns.

Sample. Participants consisted of adult men and women receiving services from Jewish Child and Family Service (JCFS). Participants were randomly selected from every service area at Jewish Child and Family Service. Service areas included newcomer settlement services, mental health, child welfare, adoption, and counselling. Except for counselling clients, all other JCFS clients must be Jewish to receive services from JCFS.

Survey Instruments. Participants completed a 7-page questionnaire that examined participants' drug and alcohol use. The questionnaire is heavily based on questions from 4 addictions measures including the South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS), Brief Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (BMAST), and the Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST).

The SOGS was developed in 1987 by Dr. Henry Lesieur and Dr. Sheila Blume for the purpose of identifying pathological gambling [10]. The present study included 4 items from the SOGS (“Have you ever gambled more than you intended to? Do you feel you have ever had a problem with gambling? Have you ever felt guilty about the way you gamble or what happens when you gamble? Have you ever borrowed money from someone to gamble or to pay gambling debts?”). The BMAST is a ten-item questionnaire widely used to assess alcohol dependence. The BMAST stems from the 25-item Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (MAST) [11]. Specifically, the BMAST assesses alcohol consumption, drinking behaviour and dependence, and consequences of drinking [11]. The DAST is a 28-item questionnaire developed by Dr. Harvey A. Skinner [12]. 13 representative items from the DAST were incorporated into the survey instrument.

The present study had an 11.5% response rate (N = 295, n = 34), which is lower than average response rate for mailed questionnaires [13], however, an acceptable sample size for a pilot study [14]. The results of analyses of correlations among income, missing work as a result of drug use, and fighting under the influence of drugs are listed in Table 1.

Correlations between income and substance use.

| Income | Marijuana use | Alcohol use | Cocaine use | Prescription medication use | General recreational drugs | Fights under the influence of drugs | Miss work | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Income | .413∗ | .383∗ | .419∗ | .418∗ | .250 | .106 | −.305 | |

| Marijuana use | .991∗∗ | .998∗∗ | .998∗∗ | .693∗∗ | .472∗∗ | .307 | ||

| Alcohol use | .991∗∗ | .991∗∗ | .673∗∗ | .452∗∗ | .296 | |||

| Cocaine use | 1.000∗∗ | .696∗∗ | .477∗∗ | .314 | ||||

| Prescription medication use | .696∗∗ | .476∗∗ | .317 | |||||

| General recreational drugs | .685∗∗ | .451∗∗ | ||||||

| Fights under the influence of drugs | .658∗∗ | |||||||

| Miss work |

The majority of respondents were female (84.4%) and nearly half (41.2%) were over 61 years old. The majority of respondents' education ranged from some university education to graduate degrees. 82.4% of respondents identified their religious affiliation as Jewish, 8.8% Catholic, 2.9% Protestant, and 2.9% Atheist. An analysis of participants by service area is provided in Table 2.

Participants by JCFS service area.

| Frequency | Percent | |

|---|---|---|

| Adoption | 1 | 2.9 |

| Counselling | 8 | 23.5 |

| Newcomers | 3 | 8.8 |

| Older adults | 11 | 32.4 |

| Protection | 1 | 2.9 |

| Volunteers | 3 | 8.8 |

| Mental health | 6 | 17.6 |

| Unspecified | 1 | 2.9 |

| Total | 34 | 100 |

41.2% reported knowing someone currently struggling with an addiction, and 23.5% of respondents reported having a family history of alcohol or drug abuse. When asked if participants or loved ones required help with substance abuse or gambling, 8.8% stated they would contact a rabbi or priest, 11.8% a CFS agency, 8.8% their doctor, 2.9% AA, 2.9% AFM, and 5.9% private counselling, and 2.9% would not seek help. 44.1% of respondents stated they would seek out multiple community resources including Alcohol Anonymous (66.6%), the Addictions Foundation of Manitoba (73.3%), private counselling (53.3%), Child and Family Service Agency (46.6%), Employee Assistance Program (20%), inpatient facilities (20%), and a rabbi or priest (20%). 35.3% of respondents reported knowing that JCFS offers JACS and 70.6% stated they would consider attending a JACS meeting. Knowing someone currently struggling with an addiction was positively correlated with knowledge that JCFS offers JACS (r = .358, p = .044). Additionally, marital status positively correlated with knowledge of addictions services at JCFS (r = .423, p = .016).

17.6% of respondents stated they have used drugs other than those required by medical reasons. 14.7% of these participants stated they cannot get through the day without using drugs and 2.9% reported neglecting their family because of their drug use. 8.8% sought help for drug use. Sex, age, marital status, and education were individually examined as predictors of alcohol and substance use; all were nonsignificant (ps > .05).

A linear regression analysis showed that knowing someone currently struggling with an addiction explains 12.8% of the variability in knowing that JCFS offers a JACS support group; F(1,30) = 4.405; p < .05. Furthermore, marital status accounts for 17.9% of the variance in knowing that JCFS offers a JACS support group; F(1,30) = 6.556; p < .05.

Research remains in its infancy on whether Jewish people feel that addictions in the Jewish community are nonexistent and therefore are not educated on the topic [5]. The current study extends this knowledge base by providing preliminary insight into the awareness of the Jewish community on others struggling with addictions, as well as services available. 41.2% reported knowing someone currently struggling with an addiction, and 23.5% of respondents reported having a family history of alcohol or drug abuse. These statistics speak to the need to further explore the Jewish community's role in recovery within the Jewish community. A statistically significant positive relationship between knowing someone struggling with an addiction and familiarity with JCFS's addictions support services is indicative of the fact that those directly affected are making an effort at identifying the resources available within their community. Marital status accounts for almost 18% of the variance in familiarity with JACS. While currently there is no research to justify these results, it is possible that concern over a spouse's behaviour as it relates to alcohol or substance use may result in increasing one's familiarity with supportive services. Significant positive relationships between income and alcohol and substance use need to be further investigated.

The present findings must be considered with regard to limitations. This study did not target a random sample and used a small subset of the Jewish community already connected with a family service agency, failing to represent the entire Jewish community. Additionally, the low response rate could be indicative of the Jewish community's lack of desire to discuss and participate in conversation and research relating to addictions in the Jewish community. Older adults accounted for the greatest responding group, which may have influenced the results.

This study provides preliminary evidence for the increasing rates of addiction in the Jewish community and the need to develop awareness in addictions services in the Winnipeg Jewish Community. It indicates that further inquiry is necessary in the areas of addiction recovery in the Jewish community. Particularly, are Jewish addicts reaching out for help within the Jewish community, is religion or spirituality a significant factor in the recovery process, and are Jewish individuals with addictions feeling supported through recovery in the Jewish community?

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

1. Veldhuizen S., Urbanoski K., Cairney J. Geographical variation in the prevalence of problematic substance use in Canada. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;52(7):426–433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2. Loewenthal K. M. Addiction: alcohol and substance abuse in Judaism. Religions. 2014;5(4):972–984. doi: 10.3390/rel5040972. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

3. Glassner B., Berg B. Social locations and interpretations: how jews define alcoholism. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1984;45(1):16–25. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1984.45.16. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

4. Weiss S., Moore M. Perception of alcoholism among Jewish, Moslem and Christian teachers in Israel. Journal of Drug Education. 1992;22(3):253–260. doi: 10.2190/50pq-ln7k-rfvj-f61n. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

5. Vex S. L., Blume S. B. The JACS study I: characteristics of a population of chemically dependent Jewish men and women. Journal of Addictive Diseases. 2001;20(4):71–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Glass C. Addiction and recovery through Jewish eyes. In: Morgan O. J., Jordan M., editors. Addiction and Spirituality: A Multidisciplinary Approach. St. Louis, Mo, USA: Chalice Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

7. The Jewish Board of Family and Children Services. JACS Meetings, http://www.jbfcs.org/programs-services/jewish-community-services-2/jacs/meetings/#.VXDIMFxVikp.

8. Engs R. C., Hanson D. J., Gliksman L., Smythe C. Influence of religion and culture on drinking behaviours: a test of hypotheses between Canada and the USA. British Journal of Addiction. 1990;85(11):1475–1482. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1990.tb01631.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

9. Steiker L. H., Scarborough B. Judaism, alcoholism, and recovery: the experience of being jewish and alcoholic. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions. 2011;11(1):90–95. doi: 10.1080/1533256x.2011.546202. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

10. Lesieur H. R., Blume S. B. Revising the south oaks gambling screen in different settings. Journal of Gambling Studies. 1993;9(3):213–223. doi: 10.1007/bf01015919. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

11. Connor J. P., Grier M., Feeney G. F. X., Young R. M. The validity of the brief Michigan alcohol screening test (bMAST) as a problem drinking severity measure. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68(5):771–779. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.771. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

12. Yudko E., Lozhkina O., Fouts A. A comprehensive review of the psychometric properties of the drug abuse screening test. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2007;32(2):189–198. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.08.002. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

13. Tse A. Comparing the response rate, response speed and response quality of two methods of sending questionnaires: e-mail vs. mail. Journal of the Market Research Society. 1998;40(4):353–361. [Google Scholar]

14. Hertzog M. A. Considerations in determining sample size for pilot studies. Research in Nursing & Health. 2008;31(2):180–191. doi: 10.1002/nur.20247. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Elana Forman, 23, hit rock bottom near Palm Beach, Florida, where she stayed in motels for two weeks with someone she met in a recovery program.

"We left treatment to go shoot up heroin, pretty much," she said. "And we were running in the streets down here. It was the worst, like, two weeks of my life. The two of us kind of went to a motel. It got really bad. We were held at gunpoint at one point."

It ended, she said, with her "back in a detox center somewhere."

Forman fought her way toward sobriety. Now more than a year and a half later, the Teaneck, New Jersey, native who goes by Ellie is a vocal member of a growing movement trying to save the lives of addicts in religiously conservative corners of Jewish America.

"The more Orthodox Jews that, you know, end up seeking help, it just raises awareness in general in the community," she said.

Elana Forman clawed her way toward the light of sobriety. Now, more than a year and a half later, the Teaneck, New Jersey, native - who now goes by Ellie - is a vocal member of a growing movement trying to save the lives of addicts in religiously conservative corners of Jewish America.NBC News

Elana Forman clawed her way toward the light of sobriety. Now, more than a year and a half later, the Teaneck, New Jersey, native - who now goes by Ellie - is a vocal member of a growing movement trying to save the lives of addicts in religiously conservative corners of Jewish America.NBC NewsIt’s not easy, Forman said, for an Orthodox-raised woman to recall a dark and shameful chapter in her life. Particularly when her journey has seen her leave Orthodox Jewish life and observancy. Starting in her early teens, Forman was keenly aware that she didn’t quite fit in with her peers.

“The Orthodox Jewish traditions and such felt constricting to me. I felt no connection to it,” she said. “I was looking for whatever else there was in this life that would fill that hole that I felt.”

That "whatever else" ended up being alcohol, weed, painkillers, heroin, and “anything offered to me,” she said.

Breaking through the silence

Talking about substance abuse and addiction in the Orthodox Jewish world is a difficult endeavor that Rabbi Zvi Gluck is well acquainted with. He grew up in the ultra-Orthodox neighborhood of Borough Park, Brooklyn and said that, “any insular community likes to remain in their bubble so that they deal with things themselves and not have to mix in the outside world into it.”

Rabbi Zvi Gluck has changed attitudes about opioid addiction in Queens, New York's Orthodox community.NBC News

Rabbi Zvi Gluck has changed attitudes about opioid addiction in Queens, New York's Orthodox community.NBC NewsGluck knew early on that helping others was his calling in life because, as he says, “at the end of the day, every time we lose somebody, no matter how old or young, you’re not just losing that person. If we can even just save one life, as the Talmud says, you’ve saved an entire world.”

In 2014, with the support of Jewish philanthropists and community leaders, Gluck created Amudim, a crisis support organization that has taken on two of the most controversial issues in the Hasidic and Orthodox Jewish worlds: sex abuse and addiction.

Since inception, Amudim has helped over 5,000 clients, from across the Jewish spectrum. They provide treatment and services for those that need help, whether they are victims of abuse or addicts. But there’s another critical component of their mission: raising awareness, battling stigma, and education.

The people Amudim serves range from 13 to 71 years old, Gluck said. Traditionally, he said, the Orthodox attitude about drug problems is to stay quiet on the issue.

"You have kids to marry off," he said, noting that recovery is a red flag for arranged marriages. "But we are noticing that a lot of the younger generation of the rabbinic leaders and the spiritual leaders do get it."

More than three out of five drug overdose deaths involve an opioid, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control. "Overdose deaths from opioids, including prescription opioids and heroin, have increased by more than five times since 1999," the CDC says on its website.

The epidemic is fueled by the over-prescription of painkillers, which can lead users to seek the cheaper and more potent opioid — heroin — on the street.

One family shares their story

Forman started her journey with addiction the night before her first day of high school, when she raided her parents’ liquor cabinet.

“I just remember being really scared about high school starting, feeling like I wasn’t going to fit in, feeling like nobody was going to like me there,” she said.

What started as a moment of escape from worries and anxiety became an addiction. And that addiction progressed from drinking and smoking marijuana nearly every day in college to using cocaine, heroin, and popping prescription painkillers.

Forman said her parents probably were unaware of her drug use, but they noticed when the requisite skirts of Orthodox Judaism gave way to jeans.

The pattern of substance abuse did eventually reach a breaking point. Forman recalled a week straight when she would go to a subway platform: “I actually remember sitting down and crying, and, like, literally just dangling my feet over the subway station. I was ready to either kill myself or to get help because I just couldn’t go on that way anymore.”

She chose to confide in her parents, Etiel and Lianne Forman.

"By the way, I'm taking a lotta drugs, and I'm, you know, I'm struggling a lot,” she said, paraphrasing her text message.

Her mother remembers that moment well. “Outwardly, we said, you know, ‘we're here for you, we wanna help you.’ Inwardly, we panicked," Lianne Forman said. "We've not dealt with this issue. We didn't know what to do, who to turn to.”

During that time, her parents learned as much as they could about addiction, and they tried not to enable their daughter. The hardest part, Etiel Forman said, was warning relatives.

"If Ellie calls you and asks you for money, no matter how plausible her excuse is, you can't give it to her," he said he told them. "To have to come to grips with the fact that your own daughter could be that desperate for that high that she would reach out to family members and lie to them and manipulate them is incredibly difficult."

Forman said that the community's focus on virtuous behavior creates a blind spot when it comes to drugs, which are "associated with prisons, with the street. "It's not something that really coincides at all with the picture of what a Jewish Orthodox person should look like," she said.

"So it's not something that's talked about in the community because people shouldn't be struggling with it," she said.

But Etiel and Lianne Forman are speaking publicly about the problem. They advocate treatment access and substance abuse education in the Orthodox Jewish world.

In April, as many as 700 people went to the Torah Academy of Bergen County, New Jersey, for an awareness event held by Amudim and Gluck. They were there to hear the Formans tell their story.

The deliberations in the Knesset Finance Committee took a personal earlier this month when lawmakers raised the issue of giving the Israel Tax Authority the right to examine private bank accounts in its battle against money laundering and tax evasion.

The idea behind the draft legislation is that the tax collectors would be alerted to possible cases by unusual activity, for instance accounts in the name of minors that suddenly get a big deposit from an overseas tax shelter like the Cayman Islands.

The proposal has aroused strong opposition out of concern it would violate the privacy rights of Israelis, even though the law would restrict the Tax Authority’s rights to exceptional cases and requires that examinations be approved in advance by the Justice Ministry. In many countries, the tax authorities have this right.

But in the finance committee it wasn’t civil rights activists who decried the injustice of the legislation, but rather two Haredi MKs — Yaacov Litzman and Moshe Gafni of United Torah Judaism. “I wouldn’t do it to my worst enemies,” Gafni told MK Nissan Slomiansky (Habayit Hayehudi), the committee’s chairman.

When Slomiansky answered, “One day you’ll have to explain to the country why this law hurts you so much personally,” Gafni countered, “The day I’ll have to explain that, you’ll be flying to the Cayman Islands.”

What exactly Gafni meant by the remarks is unclear, although the innuendo was that one or both of them had bank accounts in the Caribbean island tax shelter. But there can be little doubt that few UTJ voters have an abiding interest in the proposed legislation. Far from being concerned with being ensnared in a tax investigation, the great majority of ultra-Orthodox have incomes far too low to be paying taxes at all.

The answer to that question comes from Eitan Regev, a researcher at the Taub Center for Social Policy Studies, who in a 2014 study asked how it was possible that Israeli Haredim — the poorest population in the country — can finance the purchase of a home. Ultra-Orthodox families are not only contending with rising prices but, because they have large families, need bigger houses than other Israelis and prefer to live in specific areas where there is a big Haredi population.

Regev found that the cost of housing has caused Haredi indebtedness to grow to unsustainable proportions. That isn’t a problem exclusive to the Haredi community; Regev found that inflating housing costs have pushed many Israelis’ monthly expenses above their income, but for Haredim the red is the deepest of them all.

Reported expenses by ultra-Orthodox households exceed reported income by 3,209 shekels ($833) a month, equal to a third of their reported income and four times the shortfall that non-Haredi Jews report. It’s also 50% more than Muslim Israelis report.

“The gap between expenses and income is so wide that it suggests there is significant under-reporting of income and a major element of black market labor going on,” Regev concludes in his study.

However, the shortfall is so big that Regev assumes off-the-books jobs aren’t enough to close it and that Haredi families are making use of a gamach, a free-loan fund that is a common fixture in the ultra-Orthodox world to help people in financial distress.

Gamachim are funded by charitable contributions. While they don’t collect interest, they are for other purposes a bank that makes loans backed by guarantors. Regev estimates that anywhere between 10% and 20% of a typical gamach’s loans are never repaid, which is a very high figure.

Gamachim have grown in importance in the Haredi world in recent years. Haredim raise funds from them to accumulate enough capital to qualify for a mortgage. Regev estimates that 9% of ultra-Orthodox families have borrowed from a gamach and among the poorest the rate is 15%.

As a religious institution sanctified by tradition, gamachim are widely supported in the ultra-Orthodoxy world from the funding side, too. Some 90% of Haredim have donated to one — 42% of them giving 1,000 shekels or more — a much higher rate of giving than the 10% by non-Haredi Israeli Jews.

But the rate of contributions has been going down as the community becomes poorer. The real source of donations to gamchim comes from wealthy Haredim overseas — although much of the money being transferred isn’t charitable, according to what Regev learned from Haredi sources while conducting his research.

“Most of the respondents agree that the bulk of the money comes from loans received under the guise of donations, and that gamachim are businesses in every respect,” said Regev. “They are engaged in extensive money laundering. Most of the funds channeled to them (that is, black money) comes as loans from Jews abroad or from Haredim who live in the country but have the status of foreign residents. They transfer the funds to charitable funds from foreign accounts. It’s very difficult to track the movement of these funds.”

Police and tax investigations over the years have highlighted the role of gamachim in laundering money. For instance, a 2009 U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation probe of the Syrian Jewish community in New Jersey and Brooklyn also involved the heads of yeshivas and other Haredi institutions in Israel.

“Members of the Haredi network exploited their ability to move money through Haredi couriers who fly all over the world,” said Regev.

The method of raising money for gamachim is sophisticated. Funds from a wealthy Jew abroad will be divided between gamachim to hide its origin and the total amount involved. The money is loaned. Even if 10-20% is lost to bad loans, the cost of laundering money is relatively small.

The loans that are repaid are returned, the funds are transferred to the United Sates where they are again divided into small sums donated to local charities, which return the money to the original “donor” in the form of ruses such as inflated fees for services. “The systems works well thanks to Haredi collaboration and trust,” said Regev.

Apart from the legislation empowering the Tax Authority, the Knesset is weighing another bill that threatens to disrupt the illicit flow of money. The legislation would create a new supervisor for no-bank financial services, whose mandate would include the grey market for loans and gamachim.

Credit: Alexander Spatari via Getty Images

Credit: Alexander Spatari via Getty Images American Jews tend to be more highly educated and politically liberal than the U.S. public as a whole, as well as less religiously observant, at least by standard measures such as belief in God and self-reported rates of attendance at religious services. The U.S. Jewish population also is older than the general public and has fewer children.

American Jews tend to be more highly educated and politically liberal than the U.S. public as a whole, as well as less religiously observant, at least by standard measures such as belief in God and self-reported rates of attendance at religious services. The U.S. Jewish population also is older than the general public and has fewer children.

But within the U.S. Jewish community, one important subgroup clearly does not fit the picture of a relatively secular, liberal-leaning, aging population with small families. Unlike most other American Jews, Orthodox Jews tend to identify as Republicans and take conservative positions on social issues such as homosexuality. On average, they also are more religiously committed and much younger than other U.S. Jews, and they have bigger families.

This report uses data from the 2013 Pew Research Center Survey of U.S. Jews to look closely at the Orthodox. Information about Orthodox Jews was scattered throughout the initial survey report, “A Portrait of Jewish Americans.” It has been brought together here and supplemented with additional statistical analysis and more detailed charts and tables.

The 2013 survey found that Orthodox Jews make up about 10% of the estimated 5.3 million Jewish adults (ages 18 and older) in the United States. A survey is a snapshot in time that, by itself, cannot show growth in the size of a population. But a variety of demographic measures in the survey suggest that Orthodox Jews probably are growing, both in absolute number and as a percentage of the U.S. Jewish community.

To begin with, the median age of Orthodox adults (40 years old) is fully a decade younger than the median age of other Jewish adults (52). Despite being younger, more than two-thirds of Orthodox adults are married (69%), compared with about half of other Jewish adults (49%), and the Orthodox are much more likely to have minor children living in their household. On average, the Orthodox get married younger and bear at least twice as many children as other Jews (4.1 vs. 1.7 children ever born to adults ages 40-59). And they are especially likely to have large families: Among those who have had children, nearly half (48%) of Orthodox Jews have four or more offspring, while just 9% of other Jewish parents have families of that size.

Moreover, nearly all Orthodox Jewish parents (98%) say they are raising their children in the Jewish faith, compared with 78% of other Jewish parents. Orthodox Jews are much more likely than other Jews to have attended a Jewish day school, yeshiva or Jewish summer camp while growing up, and they are also more likely to send their children to these kinds of programs.

If the Orthodox grow as a share of U.S. Jews, they gradually could shift the profile of American Jews in several areas, including religious beliefs and practices, social and political views and demographic characteristics. Generally speaking, people who describe themselves as Orthodox Jews follow traditional interpretations of Jewish law, or halakha, and 79% of the Orthodox say that observing Jewish law is essential to “what being Jewish means” to them, personally; just 13% of other U.S. Jews say the same. On numerous measures of religious belief and practice, Orthodox Jews display higher levels of religious commitment than do other Jews.

Indeed, in a few ways, Orthodox Jews more closely resemble white evangelical Protestants than they resemble other U.S. Jews. For example, similarly large majorities of Orthodox Jews (83%) and white evangelicals (86%) say that religion is very important in their lives, while only about one-fifth of other Jewish Americans (20%) say the same. Roughly three-quarters of both Orthodox Jews (74%) and white evangelicals (75%) report that they attend religious services at least once a month. And eight-in-ten or more Orthodox Jews (84%) and white evangelicals (82%) say that Israel was given to the Jewish people by God – more than twice the share of other American Jews (35%) who express this belief.

Other U.S. Jews lean heavily toward the Democratic Party, but the opposite is true of the Orthodox. As of mid-2013, 57% of Orthodox Jews identified with the Republican Party or said they leaned toward the GOP. Orthodox Jews also tend to express more conservative views on issues such as homosexuality and the size of government; that is, they are more likely than other Jews to say that homosexuality should be discouraged and that they prefer a smaller government with fewer services to a bigger government with more services.

But just as not all Jews are alike, not all Orthodox Jews are the same. The Pew Research Center survey was designed to look at differences within the Jewish community, including between subgroups within Orthodox Judaism. About six-in-ten U.S. Orthodox Jews (62%) are Haredi (sometimes called Ultra-Orthodox) Jews, who tend to view their strict adherence to the Torah’s commandments as largely incompatible with secular society. Roughly three-in-ten Orthodox Jews (31%) identify with the Modern Orthodox movement, which follows traditional Jewish law while simultaneously integrating into modern society.

The rest of this report details some of the key differences both between Orthodox Jewish groups and among Orthodox Jews overall and other American Jews.

The 2013 Pew Research Center survey of U.S. Jews focused primarily on those who fell into two main categories. They are:

• Jews by religion – people who say their religion is Jewish (and who do not profess any other religion)

• Jews of no religion – people who describe themselves (religiously) as atheist, agnostic or nothing in particular, but who have a Jewish parent or were raised Jewish and who still consider themselves Jewish in some way

These two groups constitute, for the purposes of this analysis, the “net” Jewish population. Virtually all Orthodox Jews (99%) are Jews by religion.

These two groups constitute, for the purposes of this analysis, the “net” Jewish population. Virtually all Orthodox Jews (99%) are Jews by religion.

To identify Orthodox Jews, the survey relied on two main questions. The first asked, “Thinking about Jewish religious denominations, do you consider yourself to be Conservative, Orthodox, Reform, something else or no particular denomination?” Those who self-identified as Orthodox were then asked a follow-up question: “Do you consider yourself to be Modern Orthodox, Hasidic, Yeshivish or some other type of Orthodox?” The Haredi (or Ultra-Orthodox) category includes Jews who come from at least two distinct traditions – the Hasidic tradition and the Yeshivish (or “Lithuanian”) tradition.

How Were Today’s Orthodox Jewish Adults Raised?

The initial Pew Research Center report on Jewish Americans included a detailed look at religious switching among U.S. Jews, showing that about half (52%) of Americans who were raised as Orthodox Jews have left Orthodoxy, though most still identify as Jewish.

This report flips the lens: Among adults who currently identify as Orthodox Jews, how many were raised in the Orthodox tradition? And how many became Orthodox after having been raised as Conservative or Reform Jews, or even as non-Jews?

Seven-in-ten adults who currently identify as Orthodox Jews (70%) were raised as Orthodox. Upwards of one-in-ten Orthodox Jews (12%) say they were brought up in the Conservative movement, and 5% were raised as Reform Jews. An additional 8% say they were raised in the Jewish faith but in some other stream of American Judaism (such as Reconstructionist) or gave other answers, such as saying they were raised in a Sephardic Jewish tradition.

By comparison, the other major streams or denominations of American Judaism have smaller shares of adults who were raised in those movements: 57% of adults who identify as Conservative Jews say they were raised in the Conservative movement, and 55% of Jews who identify as Reform were raised in the Reform movement.

Family Structure and Age

Compared with other Jews, Orthodox Jews are much more likely to be married. About seven-in-ten Orthodox Jews ages 18 and older (69%) are married, compared with 49% of other adult Jews. Haredi Jews are largely responsible for this gap; 79% of Haredi adults are married. About half of adults in the Modern Orthodox tradition (52%) are currently married, comparable to the shares of adults in the Conservative (55%) and Reform (52%) traditions.

Compared with other Jews, Orthodox Jews are much more likely to be married. About seven-in-ten Orthodox Jews ages 18 and older (69%) are married, compared with 49% of other adult Jews. Haredi Jews are largely responsible for this gap; 79% of Haredi adults are married. About half of adults in the Modern Orthodox tradition (52%) are currently married, comparable to the shares of adults in the Conservative (55%) and Reform (52%) traditions.

Nearly all Orthodox Jews who are married have Jewish spouses (98%), while fewer married Conservative and Reform Jews (73% and 50%, respectively) have Jewish spouses.

Orthodox Jews not only are more likely to be married, but also are more likely to have gotten married before the age of 25. Roughly seven-in-ten currently married Orthodox Jews (68%) in the survey were married by age 24, compared with just 27% of other Jews. And while a quarter of currently married non-Orthodox Jews (24%) got married at age 35 or later, the vast majority of Orthodox Jews were married before age 35.

Orthodox Jews not only are more likely to be married, but also are more likely to have gotten married before the age of 25. Roughly seven-in-ten currently married Orthodox Jews (68%) in the survey were married by age 24, compared with just 27% of other Jews. And while a quarter of currently married non-Orthodox Jews (24%) got married at age 35 or later, the vast majority of Orthodox Jews were married before age 35.

With a median age of 40 (among adults), Orthodox Jews are younger than other Jews. Roughly a quarter of Orthodox Jewish adults (24%) are between the ages of 18 and 29, compared with 17% of Reform Jews and 13% of Conservative Jews. Moreover, only 12% of Orthodox Jews are 65 or older, while among other Jews, almost twice as many (22%) have reached the traditional retirement age.

With a median age of 40 (among adults), Orthodox Jews are younger than other Jews. Roughly a quarter of Orthodox Jewish adults (24%) are between the ages of 18 and 29, compared with 17% of Reform Jews and 13% of Conservative Jews. Moreover, only 12% of Orthodox Jews are 65 or older, while among other Jews, almost twice as many (22%) have reached the traditional retirement age.

Again, Haredi Jews stand out; 32% of Haredi adults are between the ages of 18 and 29, compared with 9% of the Modern Orthodox. Nearly half of Haredi adults (46%) are in the 30-49 cohort, while only 6% are 65 or older.

Child Rearing

Orthodox Jews tend to have more children than other Jews. The 2013 Pew Research report noted that Orthodox Jewish respondents ages 40-59 have had an average of 4.1 children in their lifetime, compared with an average of 1.7 born to all other U.S. Jews in that age group (a measure known as “completed fertility”).

Orthodox Jews tend to have more children than other Jews. The 2013 Pew Research report noted that Orthodox Jewish respondents ages 40-59 have had an average of 4.1 children in their lifetime, compared with an average of 1.7 born to all other U.S. Jews in that age group (a measure known as “completed fertility”).

Perhaps as a result of their higher rates of marriage, lower median ages and bigger families, Orthodox Jews also are far more likely to have minor children currently living in their household. About half of Orthodox adults have at least one child at home, and 19% have four children or more in the house. Haredi Jews are much more likely than the Modern Orthodox to have at least four children currently living at home (27% vs. 4%). By contrast, most Conservative and Reform Jews do not currently have any children living in their household (78% and 75%, respectively).

Nearly all Orthodox Jewish parents who have at least one child under the age of 18 living in their household (98%) are raising those children Jewish. And an overwhelming majority of Conservative Jewish parents (93%) and Reform Jewish parents (90%) with at least one child at home say they are raising those children Jewish.

Nearly all Orthodox Jewish parents who have at least one child under the age of 18 living in their household (98%) are raising those children Jewish. And an overwhelming majority of Conservative Jewish parents (93%) and Reform Jewish parents (90%) with at least one child at home say they are raising those children Jewish.

Most Orthodox Jewish parents (81%) have a child enrolled in a Jewish day school or yeshiva, compared with 11% of other Jews. And Orthodox Jews are more than twice as likely as other Jews to enroll their children in some other organized Jewish youth program, such as Jewish day care, nursery school, youth group, day camp or sleepaway camp (69% vs 27%).

Most Orthodox Jewish parents (81%) have a child enrolled in a Jewish day school or yeshiva, compared with 11% of other Jews. And Orthodox Jews are more than twice as likely as other Jews to enroll their children in some other organized Jewish youth program, such as Jewish day care, nursery school, youth group, day camp or sleepaway camp (69% vs 27%).

While most Orthodox Jews who are raising minor children send those children to full-time Jewish schools or yeshivot, other Jews are more likely than Orthodox Jews to enroll their children in other part-time formal Jewish education programs that typically supplement a largely secular education, such as Hebrew school, congregational school or Sunday school (24% vs. 16%).

Childhood Involvement in Jewish Activities

Among adults, far more Orthodox Jews attended a yeshiva or Jewish day school when they were children than did other Jews. Roughly three-quarters of Orthodox Jews (73%) say they attended a full-time Jewish school when they were growing up, compared with 17% of other Jews.

Among adults, far more Orthodox Jews attended a yeshiva or Jewish day school when they were children than did other Jews. Roughly three-quarters of Orthodox Jews (73%) say they attended a full-time Jewish school when they were growing up, compared with 17% of other Jews.

By contrast, Orthodox Jews are significantly less likely to have participated in the kind of part-time Jewish programs that typically supplement a largely secular education, such as Hebrew school or Sunday school, when they were children.

Upwards of seven-in-ten Orthodox Jewish adults (72%) say that they became a bar or bat mitzvah when they were young, compared with 48% of other Jews. And 74% of Orthodox Jews attended an overnight Jewish summer camp while growing up; among other Jews, 34% went to such a camp.

Haredi Jews are significantly more likely than Modern Orthodox Jews to report attending Jewish day school, becoming a bar/bat mitzvah or attending overnight Jewish summer camp, although majorities of adults in both groups say they had these experiences when they were children.

Socioeconomic Status

Orthodox Jews – especially Haredi Jews – tend to receive less formal, secular education than do other Jews. A third of Orthodox Jewish adults have a high school education or less, compared with just 15% of other Jews. And 30% of both Conservative and Reform Jews have post-graduate university degrees, compared with 17% of Orthodox Jews.

Orthodox Jews – especially Haredi Jews – tend to receive less formal, secular education than do other Jews. A third of Orthodox Jewish adults have a high school education or less, compared with just 15% of other Jews. And 30% of both Conservative and Reform Jews have post-graduate university degrees, compared with 17% of Orthodox Jews.

However, in terms of secular education, Modern Orthodox Jews are more similar to Conservative and Reform Jews than they are to Haredi Jews. Three-in-ten Modern Orthodox Jews (29%) have post-graduate degrees, and an additional 36% have bachelor’s degrees; among Haredi Jews, just 10% have post-graduate degrees, and an additional 15% have bachelor’s degrees.

However, in terms of secular education, Modern Orthodox Jews are more similar to Conservative and Reform Jews than they are to Haredi Jews. Three-in-ten Modern Orthodox Jews (29%) have post-graduate degrees, and an additional 36% have bachelor’s degrees; among Haredi Jews, just 10% have post-graduate degrees, and an additional 15% have bachelor’s degrees.

There are only modest differences among Jewish denominations when it comes to annual incomes. Haredi Jews are just as likely as Jews overall to report having household incomes of $150,000 or more per year, and an especially large share of Modern Orthodox Jews make $150,000 or more (37%).

Geographic Distribution

An overwhelming majority of American Haredi Jews (89%) live in the Northeast region of the country, including New York and New Jersey. Most Modern Orthodox Jews (61%) also live in the Northeast, although roughly a third live in either the South (20%) or the West (12%).

An overwhelming majority of American Haredi Jews (89%) live in the Northeast region of the country, including New York and New Jersey. Most Modern Orthodox Jews (61%) also live in the Northeast, although roughly a third live in either the South (20%) or the West (12%).

Other Jews, while still more heavily concentrated in the Northeast than the U.S. general public, are more evenly distributed across the country than Orthodox Jews. The Northeast is home to the biggest shares of Conservative (43%) and Reform (36%) Jews, but roughly three-in-ten members of each group live in the South (including Florida), and about one-in-five Conservative and Reform Jews live in the West.

Jewish Friendship Networks

Orthodox Jews, especially Haredi Jews, tend to have close circles of friends consisting mostly or entirely of other Jews. This is less common among Conservative and Reform Jews.

Orthodox Jews, especially Haredi Jews, tend to have close circles of friends consisting mostly or entirely of other Jews. This is less common among Conservative and Reform Jews.

About eight-in-ten Orthodox Jews (84%) say that all or most of their friends are Jewish. By comparison, among other Jews, about a quarter (27%) say the same.

A majority of non-Orthodox Jews in the U.S. say that at least some of their friends are Jewish, but 23% say that hardly any or none of their friends are Jewish. That is in stark contrast with the 1% of Haredi Jews and 4% of Modern Orthodox Jews who report that hardly any or none of their friends are Jewish.

Sense of Belonging and Importance of Religion

Virtually all Orthodox Jews in the survey say they have a strong sense of belonging to the Jewish people, while 73% of other Jews say the same. Similarly, more Orthodox Jews than other Jews say that being Jewish is very important to them and that they have a special responsibility to care for Jews in need.

Virtually all Orthodox Jews in the survey say they have a strong sense of belonging to the Jewish people, while 73% of other Jews say the same. Similarly, more Orthodox Jews than other Jews say that being Jewish is very important to them and that they have a special responsibility to care for Jews in need.

Followers of the major streams or denominations within U.S. Judaism are more similar when it comes to Jewish pride. Overwhelming majorities of both Orthodox Jews (98%) and other Jews (94%) say they are proud to be Jewish.

There are, at most, only modest differences between Modern Orthodox Jews and Haredi Jews on these measures of Jewish identity and belonging. Among members of both groups, big majorities say that they have a strong sense of belonging to the Jewish people, that being Jewish is very important to them, that they have a special responsibility to care for Jews in need and that they are proud to be Jewish.

The 2013 survey finds that religion plays a far greater role in the lives of Orthodox Jews than it does for other Jews. About eight-in-ten Orthodox Jews (83%) say religion is very important to them, compared with 20% of other Jews. Around the same time period, 56% of Americans overall said religion is very important in their life.

The 2013 survey finds that religion plays a far greater role in the lives of Orthodox Jews than it does for other Jews. About eight-in-ten Orthodox Jews (83%) say religion is very important to them, compared with 20% of other Jews. Around the same time period, 56% of Americans overall said religion is very important in their life.

On this question, Orthodox Jews look more like white evangelical Protestants – one of the most religiously committed major U.S. Christian groups – than like other Jews. Fully 86% of white evangelicals say religion is very important in their life.

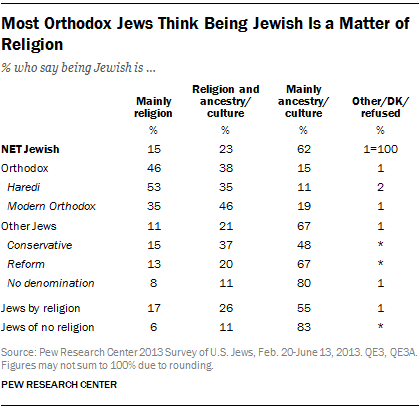

Most Orthodox Jews say that being Jewish is either mainly a matter of religion (46%) or a matter of religion as well as of ancestry and/or culture (38%). A majority of other Jews say that being Jewish is mainly a matter of ancestry and/or culture (67%); only 11% say it is mainly a matter of religion.

Beliefs and Practices

Orthodox Jews are more likely than other Jews to believe in God with absolute certainty and participate in various Jewish religious practices. For example, 89% of Orthodox Jews (including 96% of the Haredi) say they are certain in their belief in God, compared with 41% of Conservative Jews and 29% of Reform Jews. (Many Conservative and Reform Jews believe in God, but with less certainty.) And most Orthodox Jews (62%) report that they attend religious services at least weekly, compared with just 6% of other Jews.

Again, by these measures, Orthodox Jews are similar to white evangelical Protestants. For example, 93% of white evangelical Protestants believe in God with absolute certainty and 61% attend religious services weekly or more often.

Orthodox Jews are almost twice as likely as other Jewish adults to say they fasted for all or part of Yom Kippur, the Jewish Day of Atonement, in 2012 (95% vs 49%). And they are more than four times as likely as other Jews to participate in such religious practices as regularly lighting Sabbath candles, keeping a kosher home and avoiding handling money on the Sabbath. The gap between Orthodox Jews and other Jews narrows somewhat when it comes to Passover – virtually all Orthodox Jews (99%) attended a seder during the Passover previous to when the survey was conducted in 2013, compared with 66% of other Jews.

While Modern Orthodox and Haredi Jews are largely similar in their high levels of observance, lighting Sabbath candles and keeping kosher are more universal practices in Haredi homes.

Connection With and Attitudes Toward Israel

The survey finds that 61% of Orthodox Jews say they are very emotionally attached to Israel, whereas 27% of other Jews say the same. And there are significant differences between Modern Orthodox Jews and Haredi Jews on views toward Israel. Broadly speaking, Modern Orthodox Jews display stronger attachment to Israel; they are more likely than Haredi Jews to say that they are very emotionally attached to Israel (77% vs. 55%), that caring about Israel is essential to being Jewish (79% vs. 45%) and that the U.S. is not supportive enough of Israel (64% vs. 48%).

The 2013 survey also asked several questions about the Middle East peace process. It is important to bear in mind that opinions on this topic may have shifted since the survey was conducted due to events in the region (including the 2014 Israel-Gaza conflict and recent Israeli elections). As of 2013, however, there were significant differences between Orthodox Jews and other Jews in attitudes toward the prospects for peace. For example, Orthodox Jews were less than half as likely as other Jews to say that Israel and an independent Palestinian state can coexist peacefully. Non-Orthodox Jews also were much more likely than Orthodox Jews to say that building Jewish settlements in the West Bank hurts Israel’s security (47% vs. 16%).

Again, the survey found differing viewpoints within Orthodox Judaism. Roughly three-quarters of Modern Orthodox Jews (73%) said in 2013 that the Israeli government was making a sincere effort to reach a peace settlement, compared with 53% of Haredi Jews who said the same.

Social and Political Attitudes

Compared with other U.S. Jews, Orthodox Jews are far more socially and politically conservative. When the survey was conducted in 2013, 57% of Orthodox Jews said they identified with or leaned toward the Republican Party. By contrast, just 18% of other Jews identified with or leaned toward the GOP. Orthodox Jews were also much more likely than other Jews to self-identify as politically conservative (54% vs. 16%).

As on some measures of religious belief and observance, when it comes to political attitudes, Orthodox Jews resemble U.S. white evangelical Protestants. For example, 66% of white evangelical Protestants identified as or leaned Republican as of 2013, and 62% are politically conservative.

About six-in-ten Orthodox Jews (58%) say they would prefer a smaller government that provides fewer services over a bigger government providing more services, compared with 36% of other Jews who take the same position. Orthodox Jews also are far more likely than other Jews to say that homosexuality should be discouraged by society, with more Haredi Jews (70%) than Modern Orthodox Jews (38%) saying this.

Comments

Post a Comment