Bitcoin is the currency of the Russian Intelligence Services | Audio Post

Michael Novakhov's favorite articles on Inoreader

thehill.com/homenews/admin…

How Much Did Russian Spy Agencies Rely On Bitcoin?

rferl.org/a/how-much-did…

Bloomberg.com

Bitcoin Was Russian Hackers' Currency of Choice, U.S. Says

thehill.com/policy/finance…

google.com/search?q=Bitco…

-

themoscowtimes.com/2019/11/15/rus…

google.com/search?q=Bitco…

-

themoscowtimes.com/2019/11/15/rus…

A group of opposition regional lawmakers also called on Putin on Saturday to make sure Navalny is properly treated.

The post NYPD ‘Accidental’ Killer Cop’s Rise To Brooklyn Chief Questioned – Patch.com first appeared on The Brooklyn Bridge.

Google Alert – coronavirus and nypd

The post Google Alert – coronavirus and nypd: ‘We are now a lawless city’: New Yorkers left on edge as random ‘sucker-punch’ assaults known as … first appeared on The Brooklyn Bridge.

The poll also found that only 38% would support expanding the size of the court by adding four more justices. Another 42% said they would oppose doing so and the rest were unsure.

audio/mpeg 041821news01.mp3

audio/mpeg 041821news01.mp3

FILE – A Russian man identified as Alexander Vinnik, center, is escorted by police officers from the courthouse at the northern Greek city of Thessaloniki, in this Friday, Sept. 29, 2017, file photo. Vinnick, convicted of laundering $160 million in criminal proceeds through a cryptocurrency exchange, is currently imprisoned in France and might yield additional information about the intersection of organized cybercrime and the Russian state. (AP Photo/Giannis Papanikos, File)

BOSTON — A global epidemic of digital extortion known as ransomware is crippling governments, hospitals, school districts and businesses by scrambling their data files until they pay up. Law enforcement agencies have been largely powerless to stop it.

One big reason: Ransomware rackets are dominated by Russian-speaking cybercriminals who are shielded — and sometimes employed — by Russian intelligence agencies, according to security researchers, U.S. law enforcement officials, and now the Biden administration.

The value of Kremlin protection isn’t lost on the cybercriminals themselves. Earlier this year, a Russian-language dark-web forum lit up with criticism of a ransomware purveyor known only as “Bugatti,” whose gang had been caught in a rare U.S.-Europol sting. The assembled posters accused him of inviting the crackdown with technical sloppiness and by recruiting non-Russian affiliates who might be snitches or undercover agents.

Worst of all, in the view of one long-active forum member, Bugatti had allowed Western authorities to seize ransomware servers that could have been sheltered in Russia instead. “Mother Russia will help,” that individual wrote. “Love your country and nothing will happen to you.” The conversation was captured by the security firm Advanced Intelligence, which provided it to The Associated Press.

“Like almost any major industry in Russia, [cybercriminals] work kind of with the tacit consent and sometimes explicit consent of the security services,” said Michael van Landingham, a former CIA analyst who runs the consultancy Active Measures LLC.

Russian authorities have a simple rule, said Karen Kazaryan, CEO of the software industry-supported Internet Research Institute in Moscow: “Just don’t ever work against your country and businesses in this country. If you steal something from Americans, that’s fine.”

Unlike North Korea, there is no indication Russia’s government benefits directly from ransomware crime, although Russian President Vladimir Putin may consider the resulting havoc a strategic bonus.

In the United States alone last year, ransomware struck more than 100 federal, state and municipal agencies, upward of 500 hospitals and other health care centers, some 1,680 schools, colleges and universities and hundreds of businesses, according to t he cybersecurity firm Emsisoft.

Damage in the public sector alone is measured in rerouted ambulances, postponed cancer treatments, interrupted municipal bill collection, canceled classes and rising insurance costs — all during the worst public health crisis in more than a century.

The idea behind these attacks is simple: Criminals infiltrate malicious data-scrambling software into computer networks, use it to “kidnap” an organization’s data files, then demand huge payments, now as high as $50 million, to restore them. The latest twist: if victims fail to pay up, the criminals may publish their unscrambled data on the open internet.

In recent months, U.S. law enforcement agencies have worked with partners including Ukraine and Bulgaria to break up these networks. But with the criminal masterminds out of reach, such operations are generally little more than whack-a-mole.

Collusion between criminals and the government is nothing new in Russia, said Adam Hickey, a U.S. deputy assistant attorney general, who noted that cybercrime can provide good cover for espionage.

Back in the 1990s, Russian intelligence agencies frequently recruited hackers for that purpose, said Kazaryan. Now, he said, ransomware criminals are just as likely to be moonlighting state-employed hackers.

The Kremlin sometimes enlists arrested criminal hackers by offering them a choice between prison and working for the state, said Dmitri Alperovitch, former chief technical officer of the cybersecurity firm Crowdstrike. Sometimes the hackers use the same computer systems for state-sanctioned hacking and off-the-clock cybercrime for personal enrichment, he said. They may even mix state with personal business.

That’s what happened in a 2014 hack of Yahoo that compromised more than 500 million user accounts, allegedly including those of Russian journalists and U.S. and Russian government officials. A U.S. investigation led to the 2017 indictment of four men, including two officers of Russia’s FSB security service — a successor to the KGB. One of them, Dmitry Dokuchaev, worked in the same FSB office that cooperates with the FBI on computer crime. Another defendant, Alexsey Belan, allegedly used the hack for personal gain.

A Russian Embassy spokesman declined to address questions about his government’s alleged ties to ransomware criminals and state employees’ alleged involvement in cybercrime. “We do not comment on any indictments or rumors,” said Anton Azizov, the deputy press attache in Washington.

Proving links between the Russian state and ransomware gangs is not easy. The criminals hide behind pseudonyms and periodically change the names of their malware strains to confuse Western law enforcement.

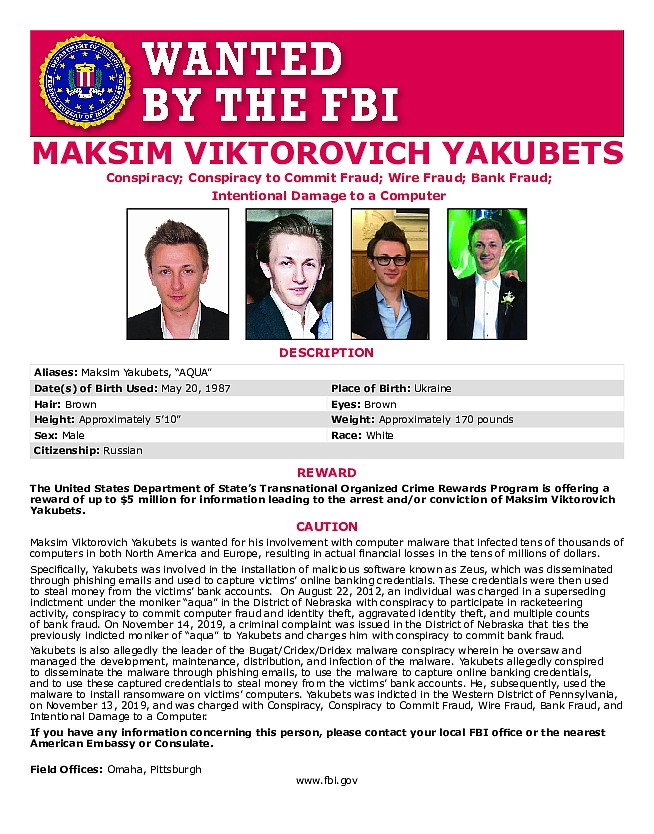

But at least one ransomware purveyor has been linked to the Kremlin. Maksim Yakubets, 33, is best known as co-leader of a cybergang that cockily calls itself Evil Corp. The Ukraine-born Yakubets lives a flashy lifestyle, He drives a customized Lamborghini supercar with a personalized number plate that translates to “Thief,” according to Britain’s National Crime Agency.

Yakubets started working for the FSB in 2017, working on projects including “acquiring confidential documents through cyber-enabled means and conducting cyber-enabled operations on its behalf,” according to a December 2019 U.S. indictment. At the same time, the U.S. Treasury Department slapped sanctions on Yakubets and offered a $5 million reward for information leading to his capture. It said he was known to have been “in the process of obtaining a license to work with Russian classified information from the FSB.”

The indictment charged Evil Corp. with developing and distributing ransomware used to steal at least $100 million in more than 40 countries over the previous decade, including payrolls pilfered from towns in the American heartland.

By the time Yakubets was indicted, Evil Corp. had become a major ransomware player, security researchers say. By May last year, the gang was distributing a ransomware strain that was used to attack eight Fortune 500 companies, including the GPS device maker Garmin, whose network was offline for days after an attack, according to Advanced Intelligence.

Yakubets remains at large. Another Russian currently imprisoned in France, however, might offer more insight into the dealings of cybercriminals and the Russian state. Alexander Vinnik was convicted of laundering $160 million in criminal proceeds through a cryptocurrency exchange called BTC-e. A 2017 U.S. indictment charged that “some of the largest known purveyors of ransomware” actually used it to launder $4 billion. But Vinnik can’t be extradited until he completes his five-year French prison sentence in 2024.

Still, a 2018 study by the nonpartisan think tank Third Way found the odds of successfully prosecuting authors of cyberattacks against U.S. targets — ransomware and online bank theft are the costliest — are no better than 3 in 1,000. Experts say that those odds have gotten longer.

The recent sanctions send a strong message, but aren’t likely to deter Putin unless the financial sting hits closer to home, many analysts believe.

That might require the kind of widespread multinational coordination that followed the 9/11 terror attacks. For instance, allied countries could identify banking institutions known to launder ransomware proceeds and cut them off from the global financial community.

“If you’re able to follow the money and disrupt the money and take the economic incentive out, that’ll go a long way in stopping ransomware attacks,” said John Riggi, cybersecurity advisor for the American Hospital Association and a former FBI official.

Information for this article was contributed by Angela Charlton of The Associated Press.

When it was seized by U.S. law enforcement in 2017, BTC-e was described as “one of the world’s largest and most widely used digital-currency exchanges.” It was also one of the most notorious.

Billions of bitcoin and other digital currencies had been swapped since BTC-e’s creation six years prior. But that was before one of its alleged founders, Aleksandr Vinnik, was arrested on a Greek beach in 2017 on a U.S. arrest warrant. The following year, Special Counsel Robert Mueller revealed precise evidence in alleging how Russia’s military intelligence agency used bitcoin transactions to mask meddling in the 2016 U.S. presidential elections.

Earlier this month, new glimpses into the shadowy world of cryptocurrencies emerged in a BBC Russian Service report that provided more indications of how exactly Russian spy agencies were intertwined with bitcoin exchanges like BTC-e.

“At a minimum, BTC-e was always heavily used by cybercriminals to launder funds, so it would have been a natural place for Russian intelligence to procure hard-to-trace funds as well,” says Kim Nilsson, a Tokyo-based programmer engineer who gained renown for helping solve a massive bitcoin theft linked to BTC-e.

“Russia’s particular interest in Vinnik’s extradition might suggest some important higher-ups may have had their fingers in the BTC-e pie, if not Russian intelligence itself,” Nilsson tells RFE/RL.

BTC-e, which was basically a giant online marketplace for buyers and sellers of bitcoins and other cryptocurrencies, had intrigued researchers, analysts, and law enforcement even before the United States seized it two years ago.

Since its inception in 2011, founded and operated by Vinnik and a partner named Aleksandr Bilyuchenko, BTC-e’s business model was heavily reliant on the criminal underworld and people and entities interested in anonymity or hard-to-trace transactions, according to U.S. and other officials.

Its website said BTC-e was located in Bulgaria, but based in both Cyprus and the Seychelles.

One researcher who tracks blockchain transactions — essentially the underlying technology that makes cryptocurrencies function — estimated that as of 2016 as much as 70 percent of all cryptocurrency criminal cases globally involved BTC-e.

That included what turned out to be the theft of around $400 million from a bigger, older cryptocurrency exchange based in Tokyo known as Mt. Gox. Uncovered in 2014 mainly by Nilsson and colleagues, the theft was the biggest involving cryptocurrencies to date, and helped pushed Mt. Gox into bankruptcy.

Investigators later found that between 2011 and 2014, BTC-e processed transactions involving funds stolen from Mt. Gox.

Three years after the Mt. Gox collapse, on July 24, 2017, Vinnik was arrested on a beach in Greece, where he was vacationing with his family. When he was taken into custody by U.S. agents, Vinnik, who was charged with 21 counts of money laundering and other related charges, was logged onto his BTC-e account on his cell phone.

According to the U.S. Justice Department, Vinnik, now 39, was allegedly the mastermind behind an international money-laundering scheme that had processed over $4 billion in cryptocurrency transactions, including bitcoins stolen from Mt. Gox.

After his arrest and the unsealing of the U.S. extradition order, Russia filed a court order in Greece seeking to have Vinnik returned to Russia, purportedly to face charges in a case of small-scale fraud. France later filed its own extradition order.

Two years after his arrest, on July 25, 2019, U.S. prosecutors filed another complaint against Vinnik and BTC-e, moving to seize about $100 million from frozen BTC-e accounts for alleged violations of U.S. banking laws.

As of this writing, he is still in Greek prison awaiting a final ruling by Greek authorities on where he will be sent.

‘The Perceived Anonymity Of Cryptocurrencies’

On July 13, 2018, almost a year after Vinnik’s arrest, the first of two U.S. indictments was unsealed, charging 12 officers from the Russian military intelligence service popularly known as the GRU with conspiracy to interfere in the U.S. political system in 2016 and other efforts. The first was brought by Special Counsel Mueller; the second, released in October, by U.S. prosecutors in Pennsylvania.

Among other things, the indictments contained precise identifying information about the GRU units allegedly involved, including a group of hackers known unofficially as Fancy Bear.

“To facilitate the purchase of infrastructure used in their hacking activity, the defendants conspired to launder the equivalent of more than $95,000 through a web of transactions structured to capitalize on the perceived anonymity of cryptocurrencies such as bitcoin,” prosecutors wrote.

The indictment also provided detailed information about the bitcoin transactions that were allegedly used by the agents.

Tom Robinson, a scientist at London-based research company Elliptic Enterprises, examined the specific transactions, and in a report published 11 days after the first indictment, concluded there was a strong link between the GRU operatives and BTC-e.

He stopped short of drawing a direct connection, however.

Robinson did not immediately respond to a message left for him with Elliptic’s spokesperson.

Heir To BTC-e

Within days after BTC-e was seized, a new Russian-based cryptocurrency exchange appeared, spearheaded, it later emerged, by one of Vinnik’s partners at BTC-e, Bilyuchenko. Another man who was a frequent trader of cryptocurrency on BTC-e, Dmitry Vasilyev, was also involved.

Like BTC-e, the exchange, called Wex, saw hundreds of millions of dollars in transactions of digital currencies.

Months after its founding, in early 2018, the exchange collapsed amid the disappearance, according to the BBC Russian Service, of some $400 million in cryptocurrency. Russian users of Wex who were unable to access their holdings filed police complaints with Russian law enforcement.

Prior to Wex’s collapse, Bilyuchenko and Vasilyev had sought out investors and patrons who could help stabilize the exchange and provide some protection from Russian security agencies, a common business practice known as a “roof.”

Among those contacted by Bilyuchenko and Vasilyev, according to the BBC, were Konstantin Malofeyev, a wealthy Russian businessman known for his ties to the Kremlin and his advocacy of conservative and nationalist causes. The United States imposed financial sanctions on Malofeyev in 2014 for his support of Russia-backed separatists fighting in eastern Ukraine.

Bilyuchenko later testified to police investigators that at around the time negotiations with Malofeyev were ongoing, he had been contacted by officials from Russia’s main domestic spy agency, the Federal Security Service (FSB).

In April 2018, Bilyuchenko testified that a man named Anton demanded that he turn over encrypted Wex assets, and the man said that the cryptocurrency would “go to the accounts of the FSB of Russia.” Bilyuchenko later said he was held in jail until he agreed to transfer $450 million in cryptocurrency.

The BBC also published a recording of a phone conversation purportedly between Bilyuchenko and Malofeyev in the summer of 2018. In the recording, a man identified as Malofeyev accuses Bilyuchenko of not transferring some of those funds.

“There is a great suspicion among all participants in the process that you have more [money] than you put on the exchange. The fact that you were tied to BTC-e is obvious, but on BTC-e it was much more than it turned out on Wex,” the man can be heard saying. “You are kept afloat because I say that you are mine and I am responsible for you.”

Neither Vasliyev’s nor Bilyuchenko’s whereabouts could be immediately determined.

According to the BBC, in late 2018 Vasilyev sold his interests in Wex to a man who is prominent among Russia-backed militias fighting in eastern Ukraine. Vasilyev was arrested in Italy in July 2019, though he was released the same month.

An e-mail sent to the press service of Malofeyev’s main investment company, Marshall Capital, was not immediately returned.

Not Just Simply Money Laundering?

Researchers and analysts have for years concluded that Russian’s leading spy agencies, the FSB and GRU, were taking advantage of the cover provided by cryptocurrency and their exchanges to fund operations.

For now, there’s scant incriminating evidence — at least publicly — that would directly expose how the money flows, something that would be of burning interest to U.S. intelligence agencies who have already concluded that the 2016 election interference campaign was authorized by President Vladimir Putin himself.

But there are also indications U.S. authorities have much greater intelligence on the cryptocurrency transactions beyond those hinted at in the 2018 indictments, according to Tim Cotten, a researcher based in Washington, D.C.

“No doubt the U.S. government, as the owners of the seized BTC-e, have much more data than could ever be hoped to be gleaned by a simple blockchain analysis about what funds were used where, when, and by who,” he wrote in a blog post in April 2019.

Cotton did not respond to e-mails seeking further comment.

Nilsson notes, “We’ve all seen plenty of indications from the U.S. intelligence community that Russian intelligence is well-versed in the use of cryptocurrency in their operations, so it should come as no surprise if they’re also involved in the shadier side of the market.”

The court filings in Vinnik’s case hint that one of the reasons the legal fight for his extradition has been so hard-fought may be because his potential value as an intelligence asset — able to provide details of BTC-e’s inner workings, and the agencies that used it.

Louis Goddard, a data investigator with the London-based corruption watchdog Global Witness and author of a recent report exposing a London financial company’s ties with BTC-e, says he has not yet seen evidence of a link between the BTC-e’s alleged operators and the Russian state.

However, “the lengths that both sides in Aleksandr Vinnik’s extradition battle have gone to — including the filing of separate criminal and civil suits in the United States and the reported lobbying of the Greek government by Vladimir Putin himself — raise questions about whether this case goes beyond money laundering,” Goddard tells RFE/RL.

Russia’s intelligence agency the Federal Security Service (FSB) could be behind the disappearance of $450 million worth of cryptocurrency from an online exchange platform, the BBC has reported.

The BBC investigation into how Wex, an online exchange for Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies, went out of business in 2018 has revealed fresh links between the platform’s demise and Russia’s security services.

One of the site’s co-founders told BBC News Russian he was forced to hand over information about customer’s digital wallets to individuals from the FSB in 2018. That information would enable them to seize the cryptocurrency which customers had saved on the platform — worth a total of around $450 million at the time.

INVESTIGATE THE TREACHEROUS, INEPT, BACKSTABBING GANG OF LIERS, PSYCHOPATHS, AND CRIMINALS calling themselves the “FBI”!

FBI=KGB!

INVESTIGATE the FBI nincompoops and G-PARAZITES!

REFORM the rotten FBI NOW, and Radically!!!

America, you deserve a much better domestic security service than this bunch of nincompoops and G-PARAZITES!

INVESTIGATE THE INVESTIGATORS!

INVESTIGATE THE INVESTIGATORS!

FBI=KGB!

America, you deserve a much better domestic security service than this bunch of nincompoops and G-PARAZITES!

REFORM!!!

The News And Times: INVESTIGATE THE INVESTIGATORS!

The epidemic of mass shootings started again, engineered by the KGB, the Russian (and other? the Israeli?) spies, agents, Fifth Columnists, etc., which are the Russian-Jewish MOB. | At least nine dead and up to 60 injured’ …

US civil unrest 2021 is incited by the hostile foreign intelligence services

Comments

Post a Comment