6:14 AM 11/25/2020 - James Bond, Sidney Reilly, and Lenin Assassination attempt - Audio Posts

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Reilly, Ace Of Spies Theme | The Brooklyn Radio

6:14 AM 11/25/2020 - James Bond, Sidney Reilly, and Lenin Assassination attempt - Google Search

Most successful conspiracies are home-cooked – designed and carried out by men and women in their own nation (that leaves aside mere assassinations or terror bombings, which are frequently committed by intruders). It’s rare to come across a full-dress conspiracy, a planned scheme to overthrow and replace a government by violence, successfully mounted by one country against another. There are examples, of course. The Anglo-American conspiracy in 1953 to oust Mossadegh’s government in Iran came off in the short term, leaving behind it hatreds and fears that still torture the region seventy years later. The Soviet Union engineered ‘regime changes’ in Eastern Europe in the 1940s, but most of them weren’t so much conspiracies as conquests: political collapses as a gigantic army approached, followed by the secret police. The record of success for the US in destabilising Latin American governments is very long, but not unbroken. Remember the Bay of Pigs.

It’s not enough to have enormous sums of cash, or weapons ready to ferry in, or satellite images of military airports and barracks, or some plausible exile who can be hurried into the presidential palace. All those are helpful. But they come second to two basic forms of knowledge. The first is self-knowledge: what the hell do you think you are doing? Are you clear about your aim, are you just getting rid of the current rulers, or installing a regime you have designed to be your obedient servant for years to come (in which case invasion might be simpler than conspiracy)? Having settled on what you want, how much blood are you willing to shed for it, and how much chaos can you handle? The second form of knowledge is about people. Secret emissaries promise that a certain army general will bring ten thousand soldiers across to you. Émigré ‘experts’ assure you that the peasantry of a certain province is itching to rise in arms as soon as you land and raise the rebel standard. How confident are you that any of this is true – or is it at best greedy con-men’s patter, at worst a trap?

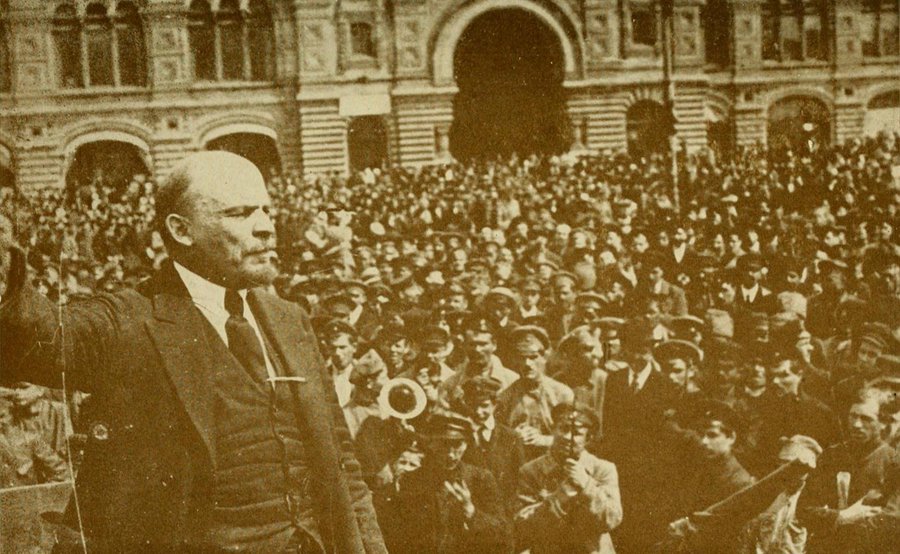

The Lockhart Plot is a book – not the first – about a very famous conspiracy by several nations against another. In 1918, Britain and France, with some American support, covertly sponsored a military plot to overthrow the Bolshevik regime in Russia, not yet a year old. The organisers accepted that this would mean eliminating its leaders, Lenin and Trotsky. Only one of the conditions for a successful external conspiracy was present. The agents on the spot in Petrograd and Moscow had quite unbelievable sums of cash to spend as bribes or to use to purchase food and weapons for the troops their Russian co-conspirators claimed to command. It was basic intelligence, above all, that was lacking. The British and French agents had no reliable information about the numbers and whereabouts of the Allied forces that were supposed to march in and support them, let alone any intelligence about the new Red Army. Their notions of levels of popular morale in different parts of Russia and Siberia were hopeful guesswork. Finally, they were never quite sure what their masters in London and Paris wanted from them. The politicians were desperately anxious not to be seen to be involved, and they also suspected that the Bolsheviks had broken their codes. Direct communication with their men ‘in the field’ amounted to mutters out of the corner of the mouth. The result was that when the plotters put some dangerous proposal to London or Paris, they came to assume that silence meant approval. That wasn’t always the case.

To Jonathan Schneer, who has taught modern history in several American universities, ‘the Lockhart Plot seemed an important subject; also, dramatic, romantic, intrinsically gripping.’ Dramatic and romantic it certainly was, and Schneer has made not one but several gripping narratives out of what he has been able to discover. This makes the book a bit disjointed. There is the story of the plot itself, as far as he can reconstruct it, and its failure. There is the Russian context of surreal confusion and bloodshed, as the Bolsheviks fought to survive and impose their authority, while their enemies – and sometimes their supposed allies – responded with local uprisings and assassination attempts (like the pistol attack on Lenin by Fanny Kaplan). And then there are the personalities. Schneer gives four of them almost lurid prominence. These are Lockhart himself; his brilliant and tempestuous mistress Moura von Benckendorff (better remembered in Britain as Moura Budberg); Feliks Dzerzhinsky, founder of the Cheka, the first version of the Soviet secret police; and Dzerzhinsky’s Latvian lieutenant, Jacov Peters. He also gives a chapter to the ungraspable rogue he calls the ‘Ace of Spies’, the man known to the Special Intelligence Service in London as Sidney Reilly. Born – maybe – as Shlomo Rozenbluim in Russian Poland, Reilly operated in a fog of rapidly changing identities and through platoons of willing girlfriends and wives (some of them bigamous).

Back in 1980, Bernard Crick began his Life of George Orwell by imploring English biographers to be honest, to confess when they didn’t know something about their subject instead of veering off into fiction. They took little notice. Schneer is endearingly open about the holes in the exceedingly tattered and piecemeal record of the Lockhart plot, some the result of weeding and redaction by intelligence services, some the work of nervous letter-burners, some just missing. When he comes to a gap, he inserts a string of ‘perhapses’ or ‘he/she would haves’ before switching on his imagination. This at least warns the reader. But it can still go over the top. There’s a sustained fantasy about what Dzerzhinsky must have thought on one particular journey: ‘He would have stared out the window, his grey-blue eyes unseeing, his quick cold brain analysing Iron Felix, cold-blooded and pitiless had sat ruminating as his train hurtled through the black night from Petrograd towards Moscow. He knew now: discriminate terror must be supplemented by terror that was indiscriminate.’ In reality, all we know about that journey is that the train arrived in Moscow and Dzerzhinsky was on it. Schneer can do better than this.

Robert Hamilton Bruce Lockhart was born in 1887, into a well-off Scottish family in Fife. Charming and intense, he studied languages and culture in Germany and France before being recruited to manage rubber estates in Malaya (a very Scottish path). Illness, probably malaria, brought him back to Britain: he joined the consular service and in 1912 was posted to Moscow as vice-consul. He soon spoke Russian like a native, and swam blissfully in the city’s prewar nightlife of vodka, champagne, Gypsy music and gorgeous women. Given to falling violently in love, he had a disconcerting way of rapidly forgetting about a lover if she wasn’t present. Schneer connects this with another weakness: his ability to shelve his own principles when duty – and career – required.

The February Revolution overthrew the tsardom in 1917; the Bolshevik seizure of power followed in November. Unlike some stuffy colleagues, Lockhart welcomed both revolutions, and his well-informed, enthusiastic reports won him respect from the leaders of the war cabinet in London. He registered early that the ‘liberal’ regime in Russia was failing, and prophesied the second upheaval. But a scandalous love affair (he was newly married) induced his ambassador to send him back to Britain. There he argued that the Bolsheviks might provide Britain with a reliable ally in the war against Germany. After Lenin took power, Lloyd George, the prime minister, sent for Lockhart and entrusted him with an extraordinary, semi-secret mission: to return to Russia as Britain’s unofficial envoy to the Bolshevik regime. In his memoirs, he wrote of this moment: ‘Adventure tugs at the heart-strings of youth I had had a colossal stroke of luck.’

Lockhart returned to Russia in January 1918. His job was to keep Russia – even a Red Russia – in the war. In Moscow, he formed a close alliance with the American Raymond Robins and a young Arthur Ransome, far the best-informed foreign correspondent in the country. Robins, a personal envoy of Woodrow Wilson’s, urged full recognition of the Bolshevik regime. Ransome, who knew the team around Lenin and had won their trust, passionately supported them. He, at least, was well aware that collapsing morale in the army meant that Russia would no longer maintain the Eastern Front against Germany. All three ‘ridiculed the charge that Lenin and Trotsky were German puppets. They believed that the Allies and the Bolsheviks could work together.’ Another member of Lockhart’s circle was the fiercely vigorous Captain Cromie, the British naval attaché, who regarded the Bolsheviks – indeed, all Russians – with contempt, but agreed on the tactical need for good relations.

Back in London, right-wing advisers were selling the war cabinet a different plan. The Allies should seize the Russian ports of Murmansk, Archangel and Vladivostok, and use them as bases to cross Russia and – with the help of anti-Bolshevik forces – re-establish the Eastern Front. Like the Americans in Iraq in 2003, the British had deluded themselves that they would be welcomed as liberators by the Russian population. Patriotic Russian soldiers, they told themselves, would be burning to resume the war against Germany.

By now, the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk had taken Russia out of the war, and German troops were surging towards the outskirts of Petrograd. In February 1918, Lockhart met Trotsky, then commissar for foreign affairs. He reported excitedly that Trotsky would accept Allied aid against the Germans and might even invite the British to occupy the ports – on condition that they renounced all co-operation with counter-revolutionary elements. ‘My policy,’ Lockhart told London, ‘promises you in a short time recommencement of war on this front.’ His cables to London became perilously big-headed for an unofficial diplomat aged only thirty: ‘If His Majesty’s government consider suppression of Bolsheviks is more important than complete domination of Russia by Germany I should be grateful to be informed.’

This cocksureness made him enemies, and events soon undermined him. Concentrating forces for Ludendorff’s final, vain offensive in the west, Germany began to withdraw troops from Russia, and the Bolshevik leaders lost interest in gaining Allied support. At the same time, the priorities of the British and French intervention plan changed. Dragging Russia back into the war gave way to the hope of overthrowing Bolshevism in co-operation with local counter-revolutionaries. A small British force landed in Murmansk, preparing to occupy Archangel; Japanese and then American troops took over Vladivostok; efforts were made to enlist the formidable Czech Legion, ex-prisoners of war who now controlled the Trans-Siberian Railway Lockhart, who at heart still felt that Russia’s future lay with Lenin and Trotsky, reluctantly admitted to himself that opposing London’s policy would cost him his career.

He was already involved with Moura von Benckendorff. It was for both of them the great love of their lives and Schneer makes a splendid story out of it, avoiding most of the conventional rubbish that gets piled up around the lives of women like her. She is supposed to have been a sexy spy for Britain, for Dzerzhinsky’s Cheka, for the Germans, for the Ukrainians No real evidence exists for any of this, though it seems that she did make some sort of bargain with the Cheka to save Lockhart’s life when he was finally arrested. In a letter to Lockhart, she described herself as a ‘big, strapping, noisy, gay creature’. But Schneer shows his readers a charming and sharply intelligent woman, better educated than Lockhart and with a wider outlook, who loved being at the centre of political intrigue and gossip and who – wherever she found herself – sailed effortlessly into the circles of ‘people who mattered’. Especially after Lockhart, she had some interesting lovers – Maxim Gorky and H.G. Wells among them. Many people told her secrets, some of which she passed on. But she had nothing in common with the code-stealing tarts of spy fiction.

Born into a landowning family in Ukraine, Budberg was married to a Russian diplomat when she met Lockhart in February 1918. In April, they became lovers, and soon were living together openly in Moscow. These were the weeks in which Lockhart began very discreetly to change sides, and to work for the Allied plan of military intervention – even if there was no invitation from Lenin’s government, and even if seizing the ports and advancing across Russia meant armed conflict with the Bolshevik regime. ‘It would be advantageous to support an anti-Bolshevik movement,’ he wrote. As Schneer remarks, he knew counter-revolution would be a by-product of this policy. There’s some evidence that his conscience troubled him. But ‘idealism warred with deceit, for every day he was smilingly and charmingly meeting with, and seeming to agree with, not only Bolsheviks but also with his friends Ransome and Robins, unreconstructed champions of Allied-Bolshevik understanding.’ Many years later, Robins described Lockhart as a ‘rat’. Schneer rather agrees.

At this point, Schneer pauses his tale to insert a sequence of profiles: Moura Budberg, of course, then Reilly, Dzerzhinsky and Peters, his Latvian deputy in the Cheka. The most interesting figure, unexpectedly, turns out to be Peters, a stocky, affable farmer’s son with (according to Bessie Beatty, an American journalist) ‘a pair of blue eyes full of human tenderness’. He seemed utterly unlike his boss, the gaunt and unsmiling Dzerzhinsky. Foreigners found that Peters enjoyed clever conversation and could be persuaded to do favours for people he liked. Before the revolution he had been married to an English banker’s daughter and lived (concealing his revolutionary views) in Islington. Peters was seen as the ‘civilised one’ among the Cheka leaders – he told Lockhart that ‘he suffered physical pain every time he signed a death sentence’ – and yet within months of the failure of the Lockhart plot, he was ‘signing away daily the lives of scores of men he never saw’. He was largely responsible for both penetrating and disabling the plot and (probably) for sparing Lockhart’s life afterwards, though Budberg’s entreaties and promises, whatever they were, clearly helped. He was a Latvian, a Lett, and kept in touch with his own small, trodden-down nation, where German occupation had replaced the Russian Empire, and he was intimate with the men of the famous Latvian Rifle Brigade, the praetorian guard of the Bolshevik revolution. A survivor of tsarist torture and imprisonment, he was above all a loyal and battle-hardened Bolshevik. But somewhere in his complicated head, the fate of Latvia also mattered. Twenty years later, Stalin’s henchmen thought so, and appear to have shot him for it.

Latvians and their Rifle Brigade were to determine the shape and then the outcome of most of the conspiracies and internal eruptions that convulsed Russia for the rest of the year. It was troops from the brigade, led by Captain Eduard Berzin, who crushed the revolt of the Left Socialist Revolutionaries in July, after they murdered the German ambassador. Meanwhile, the Allied conspiracy, now managed by an erratic caucus of Lockhart, Cromie, Reilly and the French ambassador, Joseph Noulens, was in chaos. They had assumed that the British force at Archangel, under General Frederick Poole, would advance south to seize the junction town of Vologda. His march was supposed to be timed to support counter-revolutionary risings in towns nearer Moscow, launched by their fanatical fellow plotter Boris Savinkov, who was involved in several attempted risings against the Bolsheviks. Unfortunately, General Poole failed to tell them that he had decided to postpone his offensive (he had previously requested reinforcements in the form of a brass band from Britain – jolly good for recruitment). As a result, Savinkov’s insurrections took place but were suppressed by the Red Army after brutal street-fighting.

Lockhart did not despair, though he now knew that Poole’s force was far too small to defeat the Red Army. ‘Determined, competitive, hard-nosed, capable and supremely confident, he set out to recoup the situation,’ Schneer writes. He began by hurling money around. He gave Savinkov’s clandestine National Centre a million roubles in cash, and planned – with a French colleague – to raise this to 81 million (nearly £60 million in today’s money). Then he began to think about the Latvians. How loyal were the soldiers of the Rifle Brigade to Bolshevism, now that the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk had allowed the Germans to overrun Latvia? How loyal, indeed, were they to Russia as opposed to their own country? Could they be persuaded at least to move out of Poole’s way? In Petrograd Cromie was recruiting Latvian seamen for his own plot to disable Russia’s Baltic fleet, while Reilly was saying: ‘If I could buy the Letts, my task would be easy.’ Lockhart began to look for disillusioned members of the Rifle Brigade.

Just when the Bolsheviks became aware of the plot isn’t clear from Schneer’s book. But they surely assumed its existence even before it took shape. Nothing was more inevitable than that the envoys of the ‘bourgeois imperialist Entente’ would look for ways to subvert a communist revolution and incite its opponents to rebel. The Cheka kept a close eye on the consulates and embassies in Moscow and Petrograd, noticing that counter-revolutionary leaders were using them as sanctuaries, even as bases. It wasn’t long before Dzerzhinsky knew that Lockhart was trying to subvert the Latvians. When Lenin was told about it, he ‘laughed heartily and exclaimed: “Just like in the novels!”’ Dzerzhinsky was not known for laughter, and in fact he and Peters had already set up a simple penetration scheme that soon rendered Lockhart’s operations harmless. The Lockhart Plot was from that moment doomed.

On 14 August, two Latvians – Jan Sprogis and Captain Berzin of the Rifle Brigade – called on Lockhart. The brigade was disaffected from Bolshevism, they said, and ready to help its overthrow. As Schneer writes, this seemed to Lockhart and later to Reilly like the answer to a prayer. Lockhart promised money, as well as Allied support to establish a free and independent Latvia, and wrote the visitors safe-conduct passes to reach Poole. But both men, well primed by Peters, were Cheka double-agents.

Captain Cromie in Petrograd had already been fooled by them. Now Lockhart and Reilly, with their French and American co-conspirators, fell headlong into the trap. The plot went into top gear. The Latvian Rifle Brigade would seize Vologda, opening the way for Poole and his brass band to march south. Reilly was preparing a simultaneous rising in Moscow by the White Guard, anti-Bolshevik Russian forces. From Petrograd, Cromie would fix the sabotage of Russia’s Baltic fleet. Lenin and Trotsky would be arrested, paraded through the streets in their underwear and then probably shot. Nothing that Schneer was allowed to see proves that London knew all these details, but Lockhart was obviously confident he was doing what his government wanted.

On 25 August, the plotters called a full meeting in the American consulate. More than a dozen conspirators turned up, among them (it’s not clear how he got in) the radical French journalist René Marchand. When he heard what was planned, he went straight to Lenin and Dzerzhinsky and told them everything. The Cheka was alerted that the counter-revolution was about to begin. But then events suddenly burst out of control. On the morning of 30 August, the head of the Petrograd Cheka, Moisei Uritsky, was murdered by a young poet; that evening in Moscow, Lenin himself was shot and desperately wounded by Fanny Kaplan. Neither shooting, it now seems, had any connection to Lockhart. But Dzerzhinsky and his staff assumed they did. He rushed to Petrograd; Peters ordered arrests in Moscow.

In Petrograd the next day, Cromie was persuaded by two other fake conspirators to hold a plotters’ meeting in the British Embassy. The Cheka stormed in, and Cromie (‘Clear out, you swine!’) died gun in hand. British and French diplomats and citizens were hunted down; executions began. ‘Let the iron hand of the rising proletariat fall on the vipers of expiring capitalism,’ proclaimed Jakov Sverdlov, chairman of the Central Committee.

Lockhart and Budberg were arrested the next day. Reilly vanished, resurfacing a month or so later in Sweden. Nothing was left of the plot except for General Poole, who continued to skirmish with Bolshevik forces in the Arctic north. Surprisingly, the iron hand of the proletariat treated the leading vipers quite mildly. Lockhart was transferred to a comfortable detention suite in the Kremlin and enjoyed interesting chats with Peters, during which he admitted his part in the conspiracy. Budberg, after spending a few horrible days in the Butyrka prison, brought him books and lavish supplies bought on the black market. But then the British government, terrified of what Lockhart might reveal when put on trial, did a most un-British thing: it arrested the Soviet ambassador, Maxim Litvinov, and held him with his staff as a hostage for Lockhart’s release. It worked. Lockhart was expelled, after a tearful railway-station farewell from Budberg – whom he then dumped. She recovered, and lived a long and exciting life in Russia, Italy and finally London, at the centre of a circle of ‘writers, poets, musicians, actors, directors, composers, journalists, important politicians, spies: she fascinated them all.’

Back in Britain, Lockhart drifted, drank and remarried. He wrote some bestselling books of memoir, and edited the Evening Standard’s Londoner’s Diary. There was a brief return to old skills in the Second World War; he became liaison officer to Jan Masaryk and the Czech government in exile, and then director of the Political Warfare Executive. Budberg met him again in London, after some years, and accepted a rather motherly role in a friendship that lasted until Lockhart died in 1970.

As a plotter, back in 1918, Lockhart had been smart about protecting his own security (the Cheka found almost nothing on paper that compromised him). But the conspiracy was hopelessly amateurish and leaky. More significantly, the Bolsheviks were stronger than Lockhart and his colleagues thought. Cold War histories represent them as a small, unpopular gang who carried out a coup d’état and then kept control by terror. But it’s clearer now that the internal support they had was massive and reliable, albeit nothing like a majority. Schneer writes that ‘the Lockhart Plot might have succeeded.’ It’s hard to accept he seriously believes this. Nothing in his industriously researched and usually shrewd book suggests it stood a chance. As he himself concludes, ‘Lockhart and his colleagues hoped their plot would represent a turning point in Russian, and even world history, but it was a turning point that failed to turn.’

Suspicion and vainglory, as Ronald Grigor Suny shows, were present from the start in Stalin’s approach to politics. Suny, a distinguished Soviet historian, has been working on “Stalin: Passage to Revolution” for as many years as the dictator was in power. His more than 800-page book is a half-biography, being limited to the years up to the October 1917 revolution in Petrograd. The purpose is to trace how a working-class Georgian boy in the Russian Empire rose to the height of power in the second half of his life, when he towered over Soviet politics and became one of the most murderous autocrats in world history — and to explain “why a revolution committed to human emancipation ended up in dictatorship and terror.”

The conventional picture of Stalin was first painted by his enemies. Leon Trotsky, who was assassinated in Mexico in 1940 by a Soviet NKVD agent, depicted him as talentless, a poorly educated dullard, a communist who believed in no ideology — communism included. Trotsky contended that Stalin as ruler was simply a spokesman for the oppressive state bureaucracy.

Suny, like most who have written about Stalin in the past three decades or more, finds gaping holes in that old approach. Stalin was a bright student who did well at primary school. After abandoning his training as a priest, he spent the rest of his life reading voraciously. He was an autodidact intellectual who came to adhere to the precepts of Marxism as Vladimir Lenin interpreted them. As an underground Bolshevik he developed skills as a writer, organizer and leader. Before 1917 he was not afraid to voice his opinions on the big questions of revolutionary strategy. After the Bolsheviks seized power, he showed that he could put his words into practice. Stalin was no mere pen-pusher.

The book’s strength lies not in any innovative, broad analysis but in its excavation of important episodes of the early years. Above all, Suny knows Georgia. (His sources are mainly in the Russian language, but many of them are brought to light for the first time.) Stalin, the author demonstrates, was thrashed not by his booze-soaked father but by his devout mother, Keke, who wanted to inculcate an ambition to make a better life for himself. Suny also relentlessly describes the succession of party committees that Stalin joined as he climbed the Russian Marxist hierarchy. It was a dangerous life. No revolutionary could be sure whether anyone was a true comrade or a police informer. Arrests and periods of exile were the common fate.

What I took from “Passage to Revolution” — and I agree with the idea — is that young Stalin was an angry optimist. He dedicated his time to the Marxist project when few imagined that Lenin’s Bolsheviks would ever come to power. He could have become an Orthodox priest or continued as a staff member at the Georgian meteorological observatory, but instead he channeled his ambition into the cause of revolution.

Disappointingly, the book’s final chapters reproduce a tired account of Stalin in 1917. Suny wants to judge him mainly by his willingness to recognize the genius of Lenin’s policies after his return from Switzerland in April of that year. That Lenin led a successful seizure of power is beyond doubt. It is equally undeniable that Lenin did more than anyone to get the Bolsheviks to focus on removing the provisional government that ruled after the fall of the Romanov dynasty in the February Revolution. But Lenin had to learn important lessons of his own before he could become an effective party leader. He came back from abroad spouting wild ideas about the desirability of a European civil war and a proletarian dictatorship that were unpopular with Russia’s workers. Stalin was one of the party’s leaders who got Lenin to moderate his rhetoric.

Moreover, Stalin had always been ahead of Lenin in explaining that Bolsheviks would never get the peasantry on their side unless they promised to let them take over all the agricultural land in whatever fashion they wanted. It took Lenin months in 1917 to accept this case. The political partnership between Lenin and Stalin was one of the most momentous of the 20th century, and Suny’s book fails to take its measure.

Neither Lenin nor Stalin exercised power before the October 1917 revolution — and the unanswered question is why Stalin, after rising to the apex of party leadership in the 1920s, would come to stun the U.S.S.R. with his penchant for human butchery. Does the first half of Stalin’s life allow us to predict what we all know came next? Suny is a skeptic. He rejects attempts to over-psychologize his subject while admitting that he reportedly was exceedingly antisocial in many of his traits. He stresses that Georgia was a cauldron of violence in the early 20th century but argues that this is not enough to explain the passage to the Great Terror.

His hefty, demanding tome emphasizes the effects of changing circumstances that pivoted both Stalin and Russia into a vortex of revolution and civil war. Suny leaves unexplained the mystery of why Stalin, once he achieved supreme power, went on with the killing on a scale that almost defies belief.

Stalin

Princeton.

857 pp. $39.95

Victor Sebestyen is the author of “Lenin: The Man, the Dictator, and the Master of Terror.”

THE LENIN PLOT

The Unknown Story of America’s War Against Russia

By Barnes Carr

388 pp. Pegasus. $29.95.

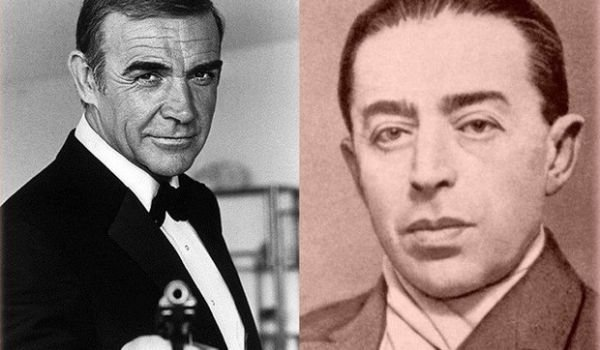

Some authors spend years on their first novel. Ian Fleming’s came in a matter of weeks. In January 1952, the middle-aged British journalist was enjoying a little winter’s sun on holiday in the Caribbean. One morning, after a swim and his usual breakfast of scrambled eggs and coffee, Fleming sat down to his battered Royal typewriter and hammered out the opening line of Casino Royale. Barely a month later, he had finished. James Bond had come to life.

Fleming went on to write a further 13 Bond novels, which have since sold more than 100 million copies globally. Big-screen adaptations have generated more than £5bn at the box office, making the Bond film franchise one of the most successful in history.

Bond is a phenomenon. It is rare to find a fictional character so intricately woven into one country’s self-image, and at the same time so hugely popular around the world. Diehard fans have ranged from the US president John F Kennedy to the North Korean despot Kim Jong-il.

These characters were not pulled out of thin air. They are an amalgam of traits that Fleming stole from a colourful cast of personalities he encountered in his own life

Bond’s extraordinary popularity is rooted in the world – and the characters – Fleming created: Bond himself, along with ‘M’, Miss Moneypenny and a rogues’ gallery of villains, including Scaramanga, Goldfinger and Blofeld. But these characters were not pulled out of thin air. They are an amalgam of traits that Fleming stole from a colourful cast of personalities he encountered in his own life. “Everything I write has a precedent in truth,” Fleming wrote. So who were the real people behind his most celebrated literary creations?

Listen: Henry Hemming discusses the real historical personalities who Ian Fleming drew on to create 007 and other characters in the Bond novels, on this episode of the HistoryExtra podcast:

James Bond – How a respected birdwatcher became the spy world’s “ultimate prostitute”

Fleming was a man of many interests, including birdwatching. That’s why he had on his bookshelf at Goldeneye, his Jamaican retreat, a well-thumbed copy of Birds of the West Indies (shown above), a field guide written by the respected American ornithologist James Bond.

Fleming later acknowledged this real-life Bond as the source of his celebrated protagonist’s name. But he did not choose it on a whim. Fleming wanted a name that was straightforward and trustworthy, and would reveal as little as possible about his character’s background. There may have also been an espionage inside-joke: ‘birdwatcher’ at the time was slang for spy. Many years later, the producers of Die Another Day (2002) made a knowing reference to this: when Bond, played by Pierce Brosnan, disguises himself as a birdwatcher, he buries himself in a copy of the original James Bond’s guide to West Indian birds.

Name aside, these two Bonds had almost nothing in common. The physical appearance of Fleming’s Bond was largely modelled on his creator. Both Fleming and Bond had blue eyes, dark hair and a “cruel mouth”. As the author admitted, however, his literary creation was much better looking.

Just as Fleming went to Eton, left early, was fatherless for most of his life, and during the war achieved the rank of acting commander in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve, so did Bond. Fleming had a love of women, fast cars, gambling and martinis – as long as they were made the right way – and for some people possessed a certain coldness or reserve; again, characteristics all ascribed to Bond.

At the same time, Fleming and Bond were very different. While the author spent most of the Second World War behind a desk, his creation was a man of action. “Bond is not in fact a hero,” Fleming explained, “but an efficient and not very attractive blunt instrument in the hands of government,” and “a meld of various qualities I noted among secret service men and commandos in the last war.” Much of Bond’s rugged adventurousness can be traced back to Fleming’s wartime encounters with intrepid soldiers and spies, including the guerrillas of 30 Assault Unit, the maverick commando group he had helped to create and run.

Ian Fleming had a love of women, fast cars, gambling and gin martinis – just like Bond

Some of those who may have directly inspired Bond’s character include Patrick Dalzel-Job, a fearless member of 30 Assault Unit; Fleming’s dashing brother Peter, who took part in covert wartime operations; and the British spy and expert skier Conrad O’Brien-ffrench, who befriended Fleming in Austria before the war.

The soldier, writer and politician Sir Fitzroy Maclean (one-time member of the SAS) and Wilfred Dunderdale, the MI6 head of station in Paris during the early part of the war, have also been put forward as possible real-life Bonds. Fleming later described Sir William Stephenson, MI6 head of station in New York, as not so much a direct model for Bond, who was “a highly romanticised version of the true spy”, but “the real thing”.

Most revealing here, perhaps, is the sheer number of people thought to have inspired the character of James Bond. Fleming made a point in his books of revealing as little as possible about the personality and background of his protagonist. The great spy writer John le Carré described Bond as “the ultimate prostitute”, in the sense that his appeal was rooted in readers never knowing too much about him, and instead being able to project their own fantasies and desires onto him, until they feel as if on one level they are him. This might explain why there is always such heated debate about which actor should next play Bond. We need it to be someone in whom we can see a part of ourselves – which is testament, ultimately, to Fleming’s achievement as a writer.

Listen: Henry Hemming describes the adventures of Sir William Stephenson, a British spymaster who plotted to bring the United States into World War Two, on this episode of the HistoryExtra podcast:

M – Authentic spymaster or family matriarch?

At first, the inspiration for M – the spy chief and Bond’s boss – appears to be straightforward. During the war, Fleming served as an aide to the director of Naval Intelligence, Admiral John Godfrey. His role involved coming up with bold deception plans, and this was the first job at which Fleming excelled, partly because he was able to put his imagination to good use, but also because he developed a good relationship with his curmudgeonly superior.

In demeanour, Godfrey was identical to M. Even the door to Godfrey’s house matches Fleming’s description of M’s door with its brass bell from a ship instead of a doorbell. The relationship between Bond and his boss is also similar to how Godfrey and Fleming collaborated.

Why did Fleming call this character M? Naturally, he wanted Bond’s boss to sound like an authentic spymaster. The head of the agency for which Bond nominally worked, the Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) – popularly known as MI6 – was called ‘C’. But as MI6 still did not officially exist, giving him this name might have resulted in a stern message from the Treasury solicitor.

Instead, Fleming went for another letter of the alphabet. He was possibly inspired by Major-General Sir Colin Gubbins, a leading figure in the Special Operations Executive, who signed his letters ‘M’. But more likely this was a nod to the best-known M in the secret service at that time: the MI5 spymaster Maxwell Knight. Since 1931, Knight had called himself ‘M’ while running his own ‘M Section’ and giving his agents codenames starting with the prefix ‘M’.

Yet there may have been another explanation. In 1917, when Fleming was still a child, his much-loved father was killed on the western front. Valentine Fleming had always been known to his children as ‘Mokie’, and some have suggested that M may be a veiled reference to him.

But could M have referred to someone else in the family? Ian’s mother, Evelyn Fleming – a strong presence in his life – was often known to her children as ‘M’. As he struggled to find a school or job that suited him, she was the one who moved him from one institution or office to another. During the 1920s and 1930s, Evelyn arranged a string of new placements and jobs for her beloved second son, many involving overseas travel, and it is easy to imagine each one resembling a fresh mission in the future author’s eyes.

Miss Moneypenny –From unrequited crush to longest flirtation in history

She may have had no more than a minor role in Fleming’s books, but after Bond himself, Miss Moneypenny is probably the most recognisable character in Fleming’s world. Appearing in every film bar two certainly helps, as does having an unforgettable name – not to mention being one half of the longest-running flirtation in film history.

The most likely model for Miss Moneypenny was Kathleen Pettigrew, secretary to C, the head of MI6, when Fleming worked in Naval Intelligence. Another possible source was Victoire ‘Paddy’ Ridsdale, who worked in the same office as Fleming. While Fleming might have wanted to have the same teasing relationship with both women as Bond did with Money-penny, there is no evidence that he achieved it. Instead, it seems Moneypenny was a (hugely successful) example of the author projecting a real-life fantasy into fiction.

Q – The lethal origins of a lovable eccentric

A fact well-known to Bondologists (less so to everyone else) is that the lovably eccentric quartermaster Q – responsible for everything from exploding tubes of toothpaste to a machine gun disguised as a set of bagpipes – never actually appeared in any of Fleming’s books. However, the novels did feature a ‘Q Branch’, and this, we know, was copied directly from real life. During the Second World War, undercover British agents bound for occupied Europe – including some of those in Fleming’s 30 Assault Unit – would pay a visit to Q (short for Quartermaster) Branch, where they were often kitted out with devices known as ‘Q gadgets’. Usually these were everyday objects adapted to contain some kind of tool or weapon, such as golf balls containing compasses; pencils hollowed out to hide silk maps; hairbrushes with saws inside; garlic-flavoured chocolate for British agents heading to France (in the hope that the smell on their breath would allow them to blend in more easily with the local population); and a shoelace that doubled up as a garotte.

The enterprising figure behind the real Q Branch was Charles Fraser-Smith. Before the war, Fraser-Smith had been a missionary in Morocco, where he and his wife ran a farm and an orphanage in the foothills of the Atlas mountains. Soon after the outbreak of war, Fraser-Smith took a job at the Ministry of Supply, where his main task was to source clothes for undercover agents travelling to Europe. But he also devised his ingenious ‘Q gadgets’, and soon had several hundred specialist companies across London. It was at this point that he met a fellow civil servant called Ian Fleming.

The villains – How Fleming got back at the bad guys

If Bond, Q, M and Moneypenny were composites of people Fleming had encountered in real life, so too were his villains. But in this case, the emotion firing the author’s imagination wasn’t so much admiration as a thirst for revenge. This certainly appears to have been the case in the creation of Ernst Blofeld and Francisco Scaramanga – the former, Bond’s nemesis in no fewer than nine films (including No Time to Die); the latter, the brilliant assassin in 1974’s The Man With the Golden Gun.

So why the names Blofeld and Scaramanga? The most convincing explanation is centred on Fleming’s nephew, Nichol Fleming, who told his uncle shortly before Ian began work on the novels that he was being bullied at school by two prefects. One of these bullies was called Blofeld – a relative of the legendary cricket commentator Henry – while the other was called Scaramanga. It turned out that Scaramanga senior had been at school with Fleming, where they had had several fights. Fleming, it seems, decided it was time to get even in print.

Fleming may also have had revenge in mind (though of a different type) when creating Auric Goldfinger, the gold-smuggling antagonist of the eponymous novel and film (released in 1959 and 1964 respectively). Like many postwar Londoners, Fleming was not fond of the work of Ernö Goldfinger, one of the modernist architects responsible for the efflorescence of tower blocks across the capital. The real-life Goldfinger was furious at the use of his name and tried to halt publication – without success.

During his career as an intelligence officer, Fleming crossed paths with a succession of large-than-life personalities, but surely none were more extravagantly weird than Aleister Crowley. And it was Crowley – sadomasochist, occultist and “wickedest man in the world” – who is thought to have inspired Fleming to create Le Chiffre, the mathematical genius with the blood-weeping eye, who appeared in the first Bond novel, Casino Royale (1953) and the 2006 film of the same name.

Fleming would have known about Crowley anyway, but the occultist came to the author’s attention personally after the unexpected arrival in Britain, in 1941, of the senior Nazi Rudolf Hess. As Fleming and others wondered what to do with the German, Crowley – who knew that Hess was fascinated by the occult – offered himself as an interlocutor. Although the idea was not as mad as it sounds, it came to nothing.

Shortly before the Second World War, Fleming met a naval officer with a moniker for the ages: Admiral Sir Reginald Aylmer Ranfurly Plunkett-Ernle-Erle-Drax. It was from this extraordinary collection of titles that the author came up with Hugo Drax, the villain who plotted Bond’s downfall in the 1955 novel and 1979 film Moonraker. Drax failed, of course, and – as he’s been doing since Fleming first brought him to life in 1952 – the world’s most celebrated spy lived to die another day.

Henry Hemming is the author of six works of non-fiction, including M: Maxwell Knight, MI5’s Greatest Spymaster (Preface Publishing, 2017)

This article was first published in the April 2020 edition of BBC History Magazine

Shared Links – Posts Review – michaelnovakhov-sharednewslinks.com | On RSS Dog | In Brief

| Michael Novakhov SharedNewsLinks michaelnovakhov-sharednewslinks.com |

|---|

| The Lockhart Plot · LRB 5 November 2020 |

| Wed, 25 Nov 2020 10:57:30 +0000 Michael_Novakhov shared this story from London Review of Books. Most successful conspiracies are home-cooked designed and carried out by men and women in their own nation (that leaves aside mere assassinations or terror bombings, which are frequently committed by intruders). Its rare to come across a full-dress conspiracy, a planned scheme to overthrow and […] The post The Lockhart Plot · LRB 5 November 2020 first appeared on Michael Novakhov - SharedNewsLinks - michaelnovakhov-sharednewslinks.com. |

| Book review of Stalin: Passage to Revolution by Ronald Grigor Suny |

| Wed, 25 Nov 2020 10:53:02 +0000 Michael_Novakhov shared this story . Suspicion and vainglory, as Ronald Grigor Suny shows, were present from the start in Stalins approach to politics. Suny, a distinguished Soviet historian, has been working on Stalin: Passage to Revolution for as many years as the dictator was in power. His more than 800-page book is a half-biography, being […] The post Book review of Stalin: Passage to Revolution by Ronald Grigor Suny first appeared on Michael Novakhov - SharedNewsLinks - michaelnovakhov-sharednewslinks.com. |

| Did the U.S. Try to Assassinate Lenin in 1918? The New York Times |

| Wed, 25 Nov 2020 10:22:09 +0000 Michael_Novakhov shared this story . Victor Sebestyen is the author of Lenin: The Man, the Dictator, and the Master of Terror. THE LENIN PLOTThe Unknown Story of Americas War Against RussiaBy Barnes Carr388 pp. Pegasus. $29.95. The post Did the U.S. Try to Assassinate Lenin in 1918? - The New York Times first appeared on Michael Novakhov - SharedNewsLinks - michaelnovakhov-sharednewslinks.com. |

| Who Was James Bond Based On? The Real Inspirations For Flemings Characters |

| Wed, 25 Nov 2020 09:46:36 +0000 Michael_Novakhov shared this story from HistoryExtra. Some authors spend years on their first novel. Ian Flemings came in a matter of weeks. In January 1952, the middle-aged British journalist was enjoying a little winters sun on holiday in the Caribbean. One morning, after a swim and his usual breakfast of scrambled eggs and coffee, Fleming […] The post Who Was James Bond Based On? The Real Inspirations For Fleming's Characters first appeared on Michael Novakhov - SharedNewsLinks - michaelnovakhov-sharednewslinks.com. |

Tweets by @mikenov

They saw him coming https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v42/n21/neal-ascherson/they-saw-him-coming …

- Michael Novakhov Retweeted

Too often, women are insulted, beaten, raped, forced to prostitute themselves.... If we want a better world, that will be a peaceful home and not a battlefield, we all need to do a lot more for the dignity of each woman.

- Michael Novakhov Retweeted

World's largest maker of PPE latex gloves shuts down half its factories after 2,500 employees are infected with coronavirus https://trib.al/zWwL8nK

James Bond in real life: where did Ian Fleming's inspirations come from? HistoryExtra

https://www.historyextra.com/period/20th-century/james-bond-who-based-on-inspiration-ian-fleming-villains-q-m/ …12:21 PM 11/24/2020 - Headlines Review https://bklynradio.com/1221-pm-11-24-2020-headlines-review/ …

- Michael Novakhov Retweeted

Former Pentagon chief Mattis calls for end to Trump’s ‘America first’ approach https://go.shr.lc/3nPOczK

Opinion | Should Trump Be Prosecuted? https://michaelnovakhov-sharednewslinks.com/trump-prosecution-html/ …

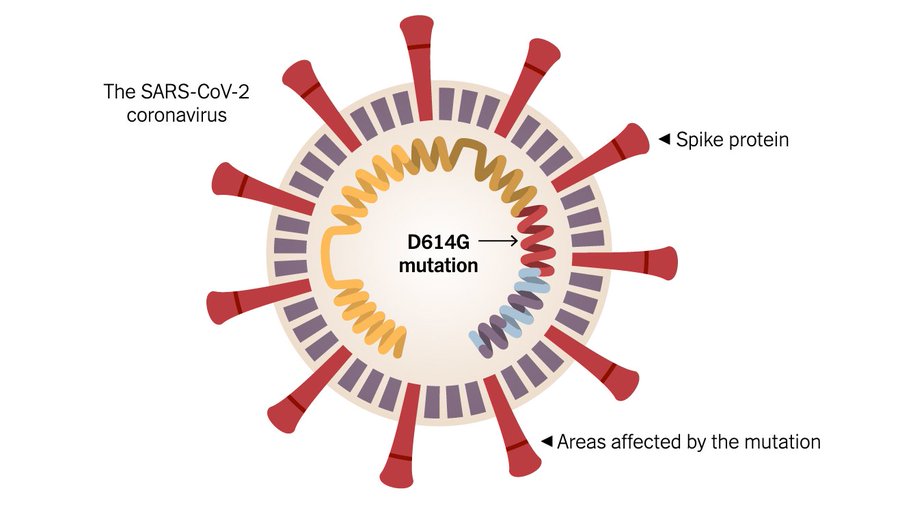

614g mutation as the German mutation - Google Search https://www.google.com/search?q=614g+mutation+as+the+German+mutation&source=lmns&bih=762&biw=1474&rlz=1C1CHBF_enUS733US733&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjDyY7_rpvtAhVBl-AKHWTJBf0Q_AUoAHoECAEQAA …

614g mutation - Google Search https://www.google.com/search?q=614g+mutation&source=lmns&bih=762&biw=1474&rlz=1C1CHBF_enUS733US733&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwj02Z_6rZvtAhWHPt8KHXhDA8kQ_AUoAHoECAEQAA … “When all is said and done, it could be that this mutation is what made the pandemic,” Dr. Engelthaler said.

Covid-19 News: Live Updates – The New York Times | Michael Novakhov - SharedNewsLinks℠ - http://michaelnovakhov-sharednewslinks.com https://michaelnovakhov-sharednewslinks.com/covid-19-coronavirus/ … “When all is said and done, it could be that this mutation is what made the pandemic,” Dr. Engelthaler said.

A Failed Attempt to Overturn the Election - 6:28 AM 11/24/2020 - The New York Times https://thenewsandtimes.blogspot.com/2020/11/a-failed-attempt-to-overturn-election.html …

- Michael Novakhov Retweeted

Russia's Sputnik V coronavirus vaccine is 95% effective, its developers said Tuesdayhttps://www.themoscowtimes.com/2020/11/24/russia-says-its-sputnik-v-coronavirus-vaccine-95-effective-a72135 …

6:28 AM 11/24/2020 - The New York Times Front Page Audio Review | Tweets by @mikenov https://bklynradio.com/628-am-11-24-2020-the-new-york-times-front-page-audio-review/ …

- Michael Novakhov Retweeted

President Vladimir Putin will not congratulate U.S. President-elect Joe Biden even though the Trump administration has approved the formal presidential transition processhttps://www.themoscowtimes.com/2020/11/24/putin-still-wont-congratulate-biden-despite-start-of-formal-transition-a72133 …

A Failed Attempt to Overturn the Election https://ino.to/YSiKzKW

4:02 AM 11/24/2020 https://bklynradio.com/402-am-11-24-2020/ …

- Michael Novakhov Retweeted

Queen Elizabeth II has granted Russian-British media mogul Yevgeny Lebedev the title of “Baron of Hampton and Siberia.” The Russian businessman is due to be sworn in as the first Russian member of the House of Lords next month https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2020/11/24/yevgeny-lebedev-named-baron-of-hampton-and-siberia-in-britain-a72129 …

‘4:02 AM 11/24/2020 - Selected Articles – Headlines Review’ on #SoundCloud #np https://soundcloud.com/mike-nova-3/402-am-11242020-selected-articles-headlines-review …

U.S. Presidential Transition begins https://www.voanews.com/episode/us-presidential-transition-begins-4482591 …

Have you heard ‘1:16 AM 11/24/2020 – News Review’ by Mike Nova 2 on #SoundCloud? #np https://soundcloud.com/mike-nova-3/116-am-11242020-news-review …

Current News Review – http://newsandtimes.org – 12:34 AM 11/24/2020: National security experts call on GOP leaders to rebuke Trumps election claims https://thenewsandtimes.blogspot.com/2020/11/current-news-review-newsandtimesorg.html …

National security experts call on GOP leaders to rebuke Trumps election claims - 12:34 AM 11/24/2020 - Current News Review – http://newsandtimes.org https://michaelnovakhov-sharednewslinks.com/national-security-experts-call-on-gop-leaders-to-rebuke-trumps-election-claims-1234-am-11-24-2020-current-news-review-newsandtimes-org/ …

National security experts call on GOP leaders to rebuke Trumps election claims - 12:34 AM 11/24/2020 - Current News Review – http://newsandtimes.org https://michaelnovakhov-sharednewslinks.com/national-security-experts-call-on-gop-leaders-to-rebuke-trumps-election-claims-1234-am-11-24-2020-current-news-review-newsandtimes-org/ …

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Comments

Post a Comment